Elections

Instead of having The Boss Decide™, use this facilitation method to make the wisest decision possible with the minimum amount of preparation and politics.

Why use this?

Elections are an alternative to normal, usually tacit methods for deciding who should do the work. Note that I’m emphasizing should: the idea is not to get to who wants to do the work, or who has to do the work, but rather the best possible person to do the work right now.

Run elections this way, because most alternatives encourage gaming, bias, and politics. This is also known as business as usual.

What are Elections?

It is a structured group facilitation method for gathering emergent wisdom from the group with the minimum amount of preparation. That wisdom is used by the facilitator to recommend who gets to fill the role or job. For small, well-practiced groups, it can take as little as 15 minutes per role to be elected. For larger groups, budget at least an hour per election.

What can Elections replace?

The Boss Chooses By Themselves™ can work well with great, informed, openminded bosses. Most of the structured steps below are the ones that good managers undertake anyway – gathering data, canvassing, making their inputs and ultimate decision clear. This is a fragile system, though – it requires substantial training and maintenance.

Direct voting and instant runoff voting (IRV) encourage folks to campaign outside of the process. It seems fairer to do it this way, but it doesn't end up any different from how it works “normally,” where folks spend weeks, months, years, careers! working toward a given position. It just makes it public, and reduces the wisdom of the group to a) what individuals say their capabilities are and b) the tally-able votes of individuals. If you’re trying to level the playing field and make the wisest decision, voting methods aren’t the way forward. IRV adds a bit more data – ranked preference – but it also means educating people on the system and finding a digital method to tabulate the votes...and eventually dealing with a culture of gaming the ranked voting system. The juice isn't worth the squeeze.

Committee Selection can yield similarly wise results to the method outlined below, but doesn't do much to resolve politics and gaming. Also – who chooses the committee? What method do they use? Good committees make this transparent, but again – this is fragile and subject to change.

Instead, why not commit as a group to follow a process?

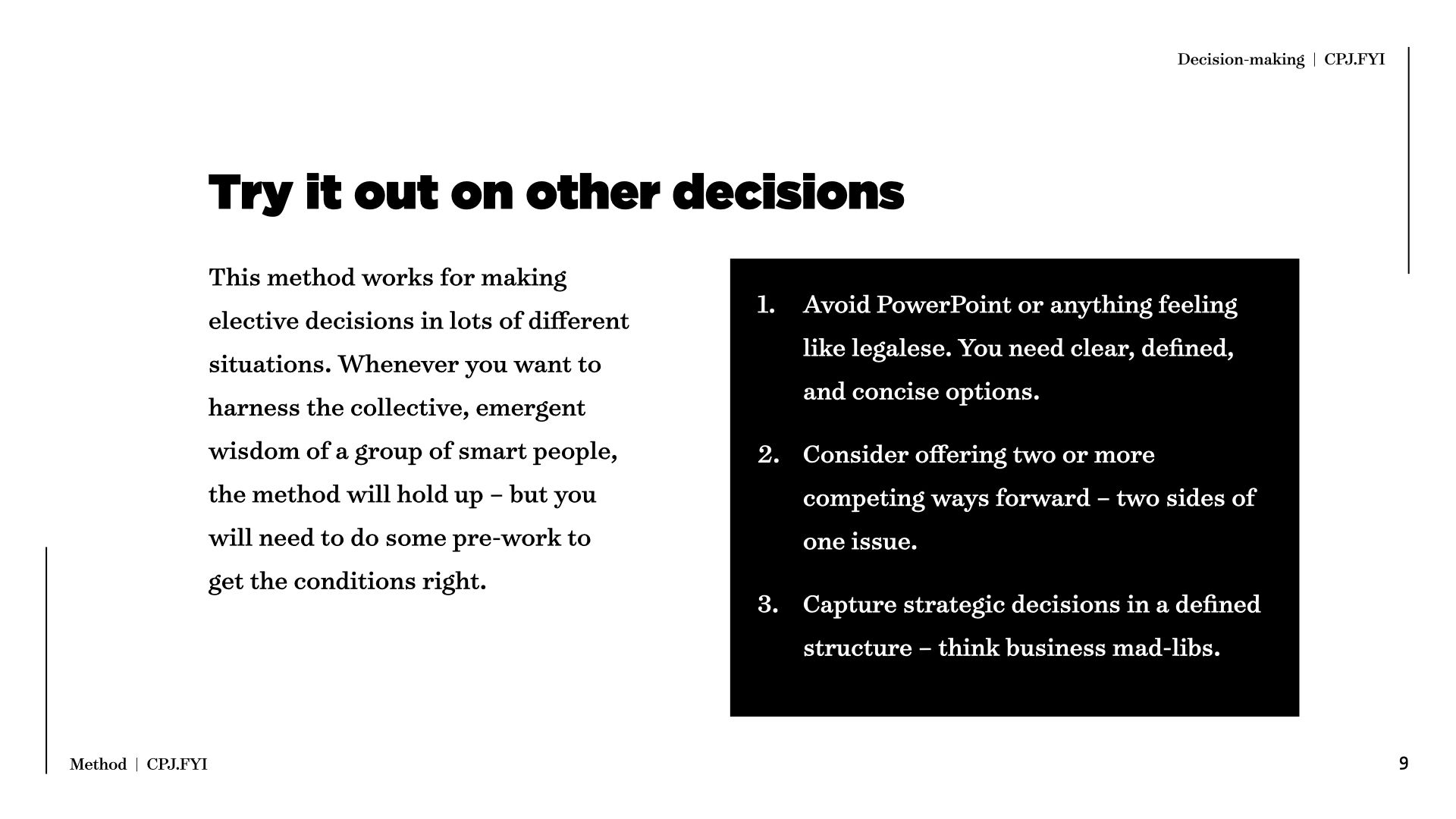

Use Elections for any important decision. It doesn't need to be exclusive to electing humans to fill roles – it can also be used to pick between strategic or tactical options – all you need is a clear problem statement, to replace the "role to be filled" and a set of concise options for how to move forward, to replace the "candidates."

Method

Click/Tap to Embiggen

Explainer

Preparation

- A clear role description: obvious but overlooked. Most role or job descriptions are overlong, under-describe outcomes, and over-prescribe actions, but we'll save that for another guide. One very helpful thing to consider when crafting the role for election: what's the duration of the appointment?

- Time for making the decision. There are five (optionally six) steps to the process; for each role that you're electing, budget a baseline of 15 minutes plus five minutes per person in the group. For a team of seven people, that's about 50 minutes. Teams get better at this over time, and wiser about who should do what, so don't let this time budget get you down. This leads to...

- A list of participants and an invitation to participate. If the list of participants is more than nine people, consider ways to shortcut some of the steps: gather nominations and rationales (Steps 1 and 2) via a survey, and circulate a readout of those nominations/rationales before jumping straight into Step 3.

- A method for gathering and sharing nominations in the moment. Email or private messaging will do for remote groups; scrap paper or post-its works well for in-person groups. Video-conferencing is important but not essential for the quality of the decision.

- A decision for who will facilitate. This is a big one. For groups new to elections, I recommend the person with the most positional authority to start; this will shortcut questions of legitimacy. Eventually, groups should elect their facilitator, and that person should hold the role for at least a quarter.

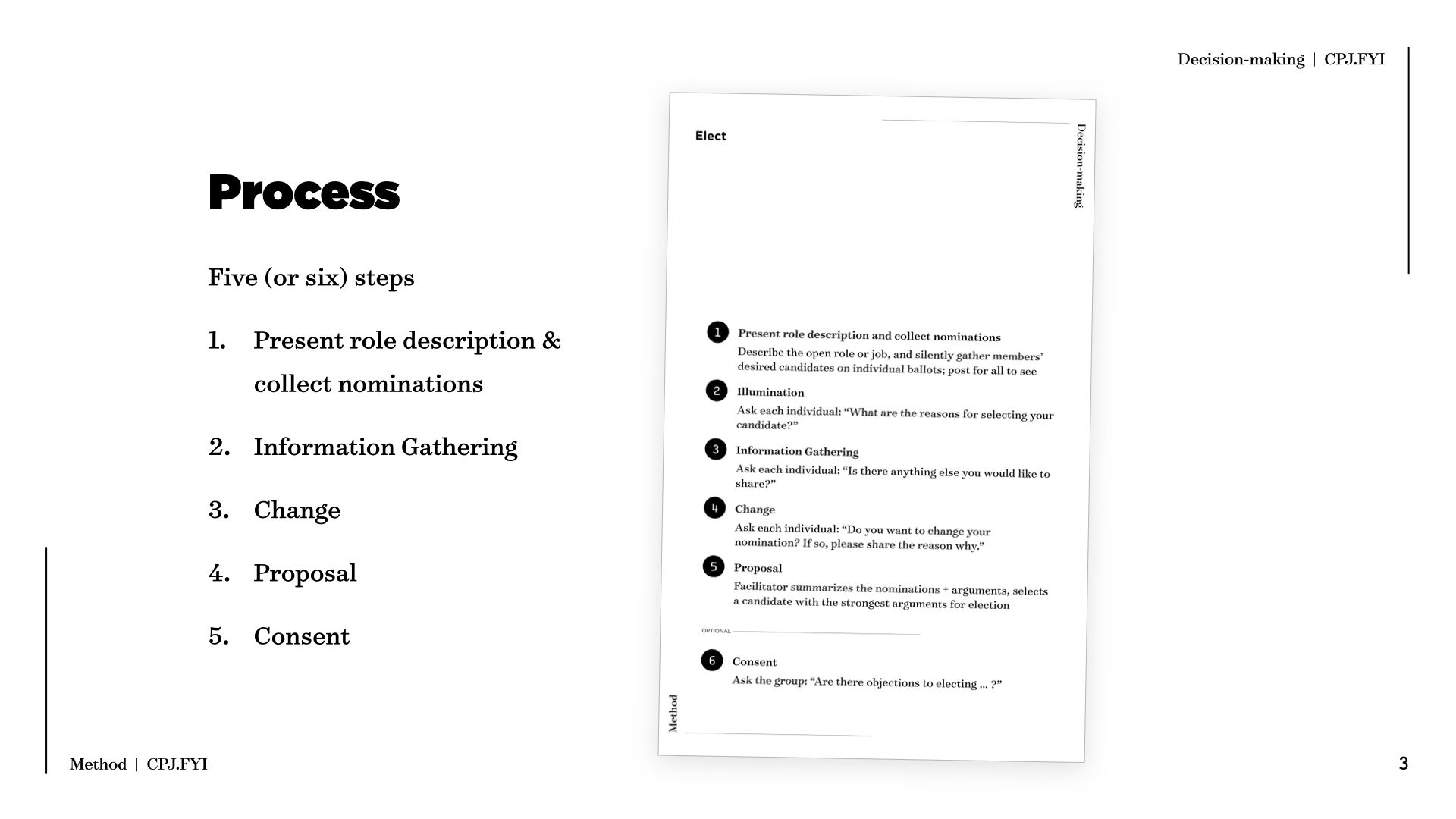

Step 1: Present role description and collect nominations

Describe the open role or job, and silently gather members’ desired candidates on individual ballots; post for all to see

Spend whatever time is necessary getting clear with the group what work is before collecting nominations. Allow questions and discussion if it's helping the group get clarity.

As a facilitator, the main concern in the collecting-ballots moment is doing so in a way that the group doesn't anchor around a particular candidate – anchoring will reduce the quality of the decision. Remember: we're not looking to find out who wants to do a job, we're looking to determine who should do the job. Put the nominations up where folks can see them – for example, on a text file that you share on screen if any of your participants are remote.

Be sure to identify who made what nomination. This is important for all of the later steps of the process.

As the facilitator, it's up to you (or the presiding team rules, if they exist) whether you participate in the nominating. You'll be making the final recommendation to the team, so your participation may indicate bias – have a think about this.

Step 2: Illumination

Ask each individual: “What are the reasons for selecting your candidate?”

Once everyone can see everyone else's nominations, ask each participant to share only positive reasons why they selected their candidate, and not share reasons why they didn't select someone else. As a facilitator, don't let folks interrupt each other or ask questions for clarity. The rest of the steps will get folks the clarity they need, and once everyone has shared, there will be enoughinformation in the room to make a high-quality decision. Let folks pass if they need more time to think, but be sure to remember to come back to them.

For this step and the next, it's not necessary to capture any notes or verbatim responses to the prompt, unless that's necessary to accommodate for individuals in the group. Most organizations don't need or ever use a record of the inputs to the election – I recommend just capturing the outputs.

As a facilitator, though: jot down some rough bullet-point notes to yourself to aid in your summarizing and recommending in Step 5.

Step 3: Information Gathering

Ask each individual: “Is there anything else you would like to share?”

Now is a chance to bring the overall context into the decision – if you think it's important that folks know why they shouldn't choose a particular candidate, this is the time to bring it up. There's no need to remind participants of this – simply asking if there is anything else will prompt the right information. Again, don't allow interruptions, questions, or discussion, and allow folks to pass if necessary.

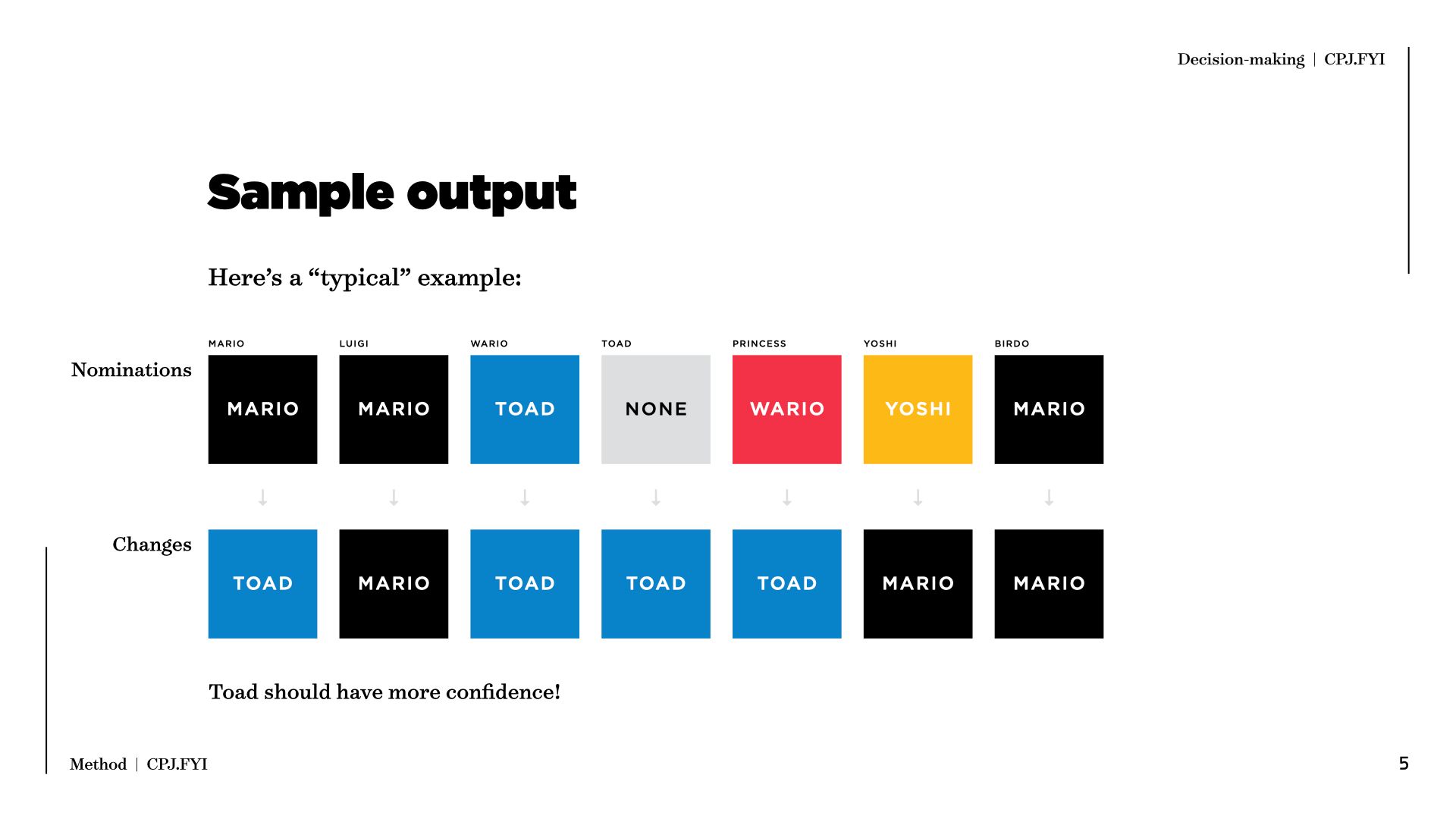

Step 4: Change

Ask each individual: “Do you want to change your nomination? If so, please share the reason why.”

Now, with ample data to support a wise decision, ask each person in turn whether they would like to change their nomination. As a facilitator, capture the changes as they happen. A few things to consider here:

- Remote groups can use co-working software, like Google Drive, to collaboratively edit their nominations on a shared screen.

- Well-practiced groups will want to speed through this round, readily accepting a growing "wisdom of the group." Let them follow this instinct to go with the flow, unless you sense that individuals are being railroaded into a decision that they don't believe in.

Step 5: Proposal

Facilitator summarizes the nominations + arguments, selects a candidate with the strongest arguments for election

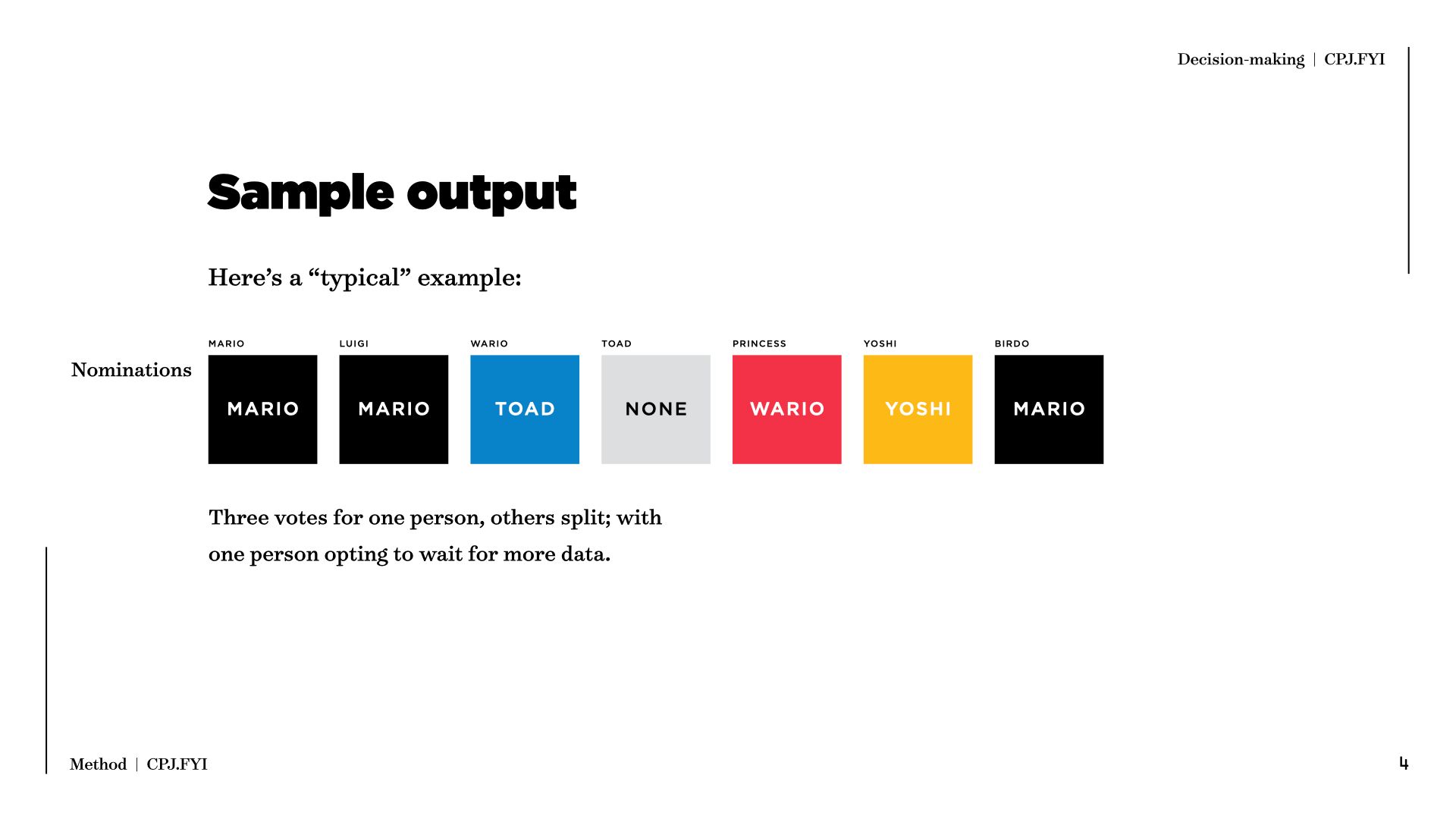

The four preceding steps will yield a shortlist of nominees – usually three at most, usually with a clear majority opinion. It's up to the facilitator to summarize the arguments made by the group and select a candidate.

For many groups, especially those where the person with the most positional authority is the facilitator, the process can end here: the boss has made an informed decision about who should do what. It should progress naturally to a small round of applause for the person selected.

For an elected facilitator, this is a heavy, important, cognitive and emotional task. They're being asked by their peers (or in some cases, superordinates or clients!) to make a career decision for the group. If this is you: step into this role with confidence – the people want you to do this for them. And if you're concerned with fairness, understand two things:

- How fair was the process before? Is this more or less fair, in general?

- There is a ton of social pressure and group supervision built into this process – it would be extremely unlikely for a facilitator to go against the wisdom of the group.

If you're still concerned, add a sixth step:

Optional Step 6: Consent

Ask the group: “Are there objections to electing … ?”

Check with the group to see if there are any objections. This is the last chance to ensure the right person is being elected to do this work, at least until we can gather again when we have more data. Leave some open air to encourage people to jump in if there are objections – reasons why this is an unsafe thing for us to do – and spend time discussing, as a group, how to resolve these objections. Some tips:

- Ask folks with objections to offer a counter-proposal, and then ask the group if there are any objections to this new way forward

- If there's no counter-proposal, dig into the objection to find the root of it. Look for reasons why this is an unwise choice for the business or the outcomes the org is trying to achieve and resolve those – avoid solving for preference.

- Default to time limitations – can we come back in a month, or a quarter, to revisit this decision?

Along the way, look for nonverbal cues that the group is making a bad call – crossed arms, posture changes, sighs, checked-out eyes. If you're getting this feeling, check-in with folks that are checking-out.

Comments