Flattening

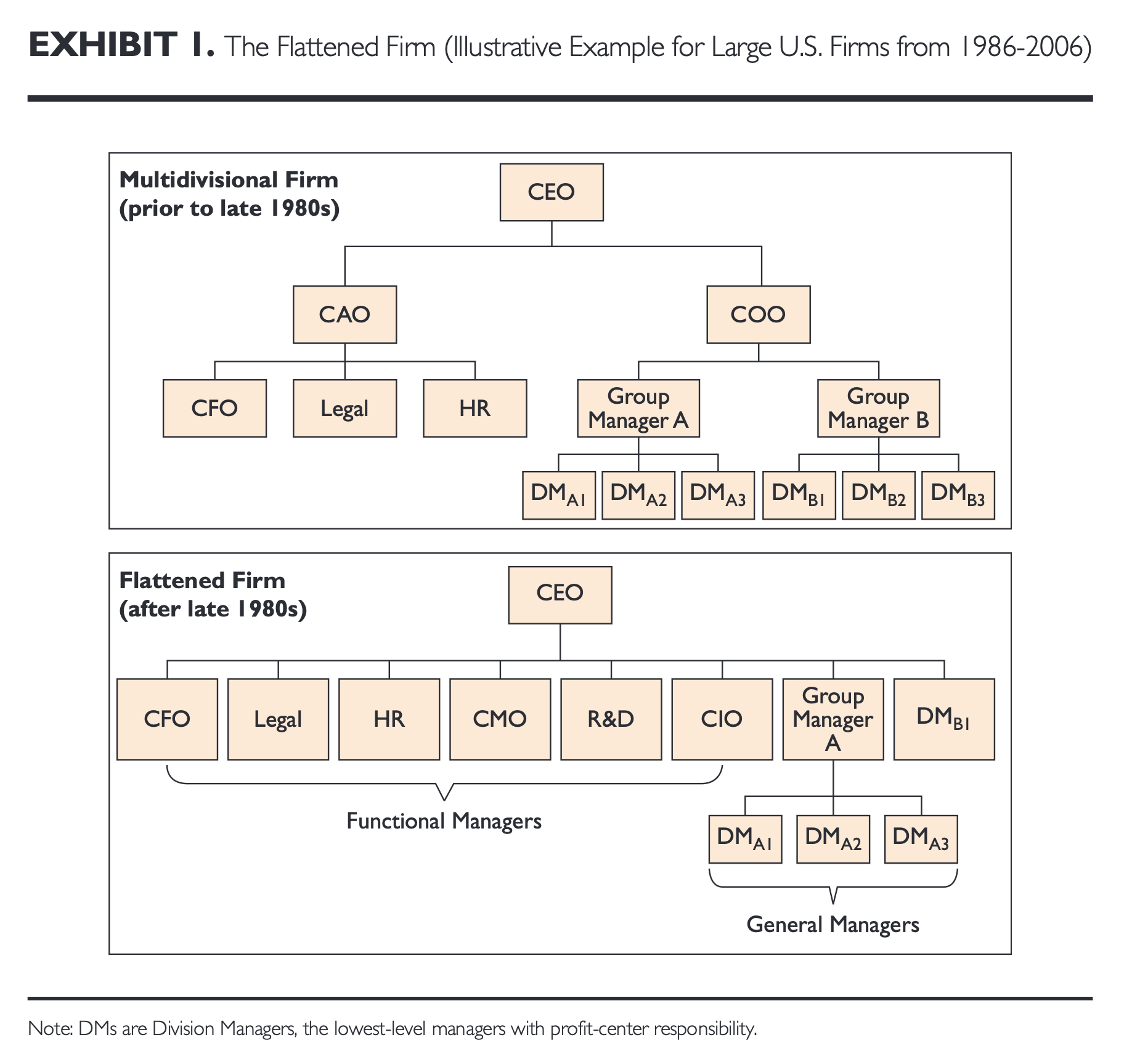

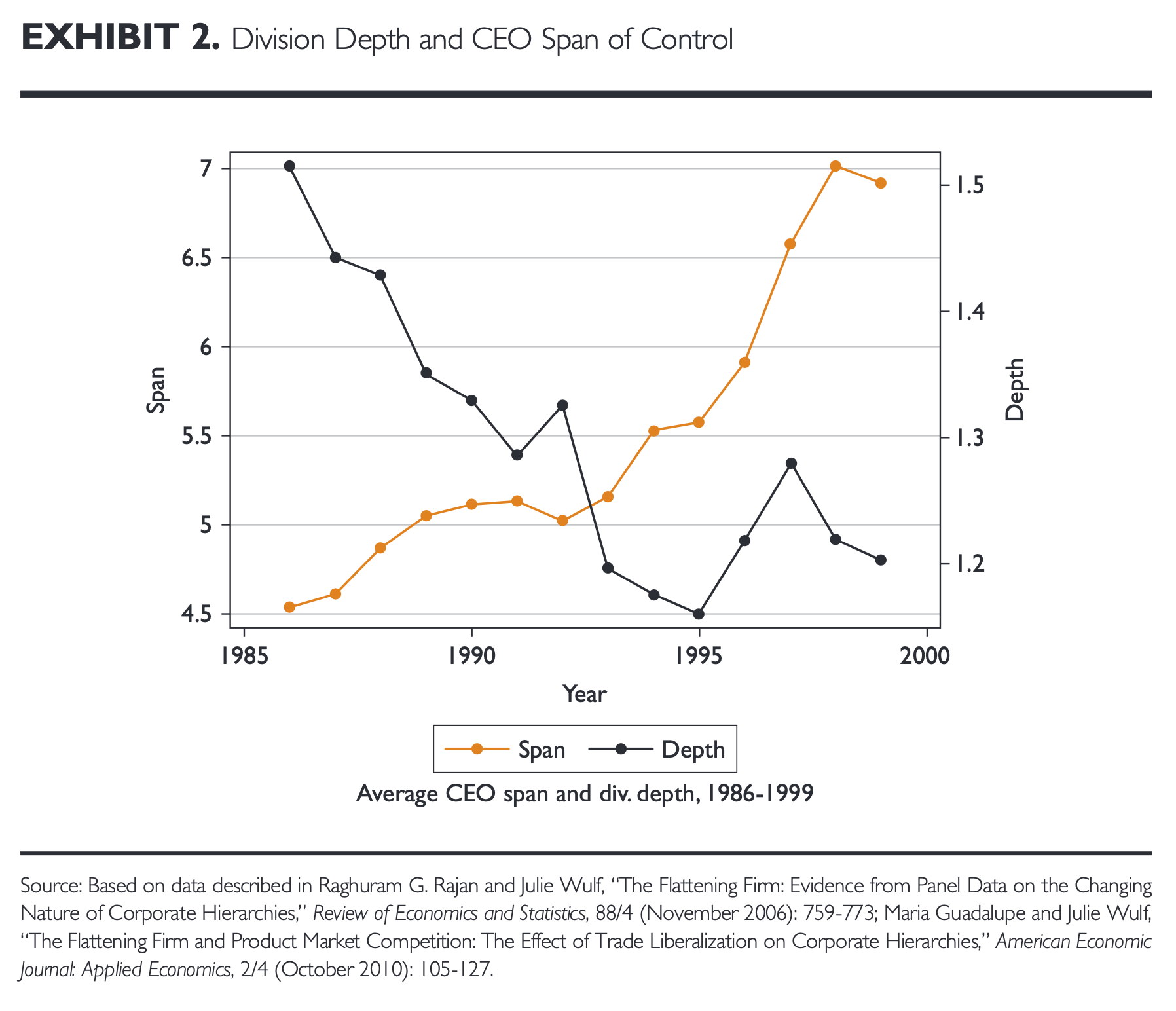

Basic premise: because technology (and other factors), firms were able to flatten, putting more managers under the direct control of a senior leader.

Via CV Harquail, I found this gem: “The Flattened Firm: Not as Advertised.” I’d call it a must-read. TLDR version below. Everyone talks about flat structures being great. But “flat” actually just means “more centralized control by fewer people.”

The study looked primarily at the C-suite, but the principle of more span per leader and less depth in general cascades all the way through modern organizations.

“Our main insight from the interviews is that flattening is not about delegation of decision making to subordinates and a hands-off role for the CEO. In fact, the most consistent message from the CEOs was that they had changed the structure of their executive team and broadened their span of control to “get closer to the businesses. They or their predecessors had eliminated the COO position in pursuit of more control, more oversight, and more involvement in business operations and decisions, not less.”

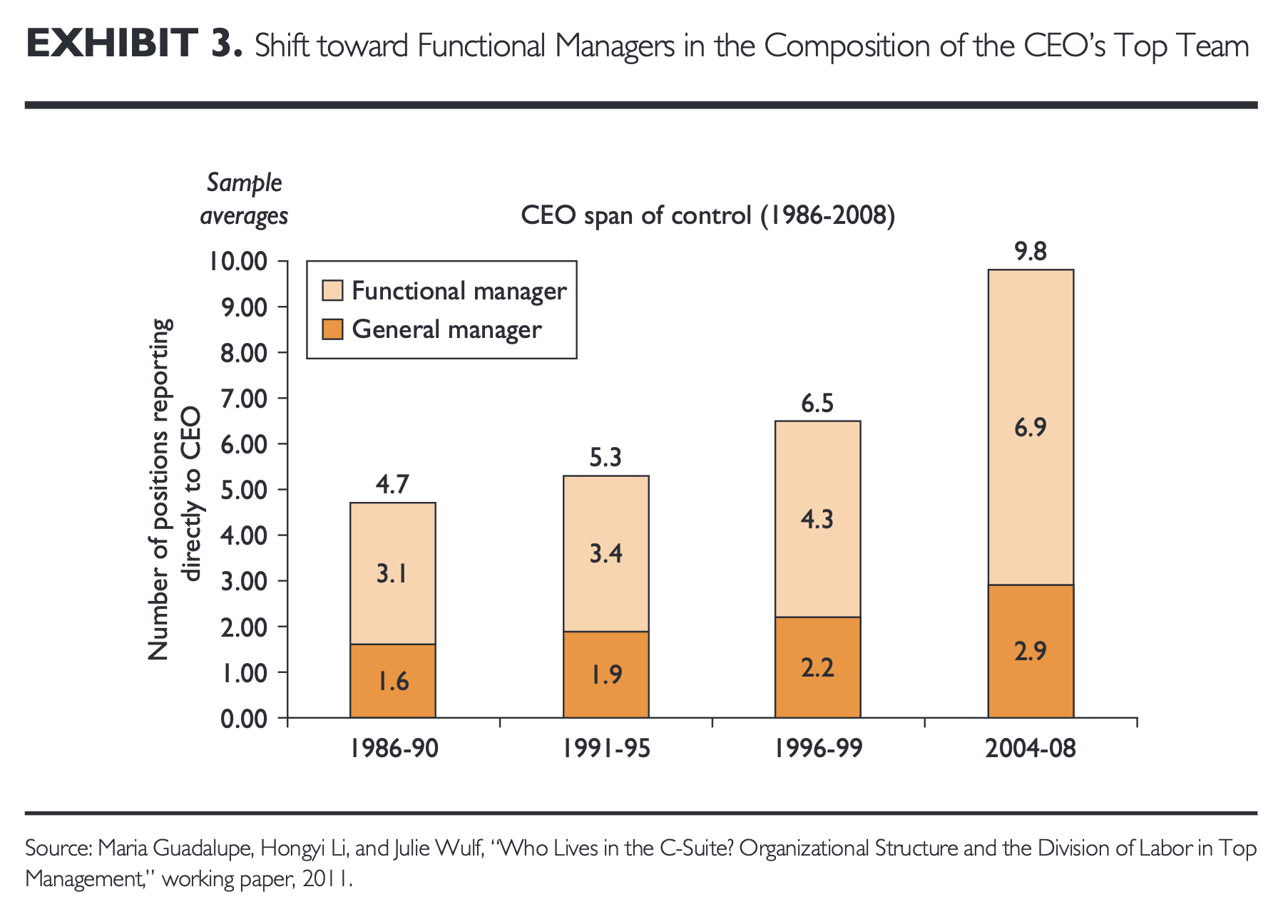

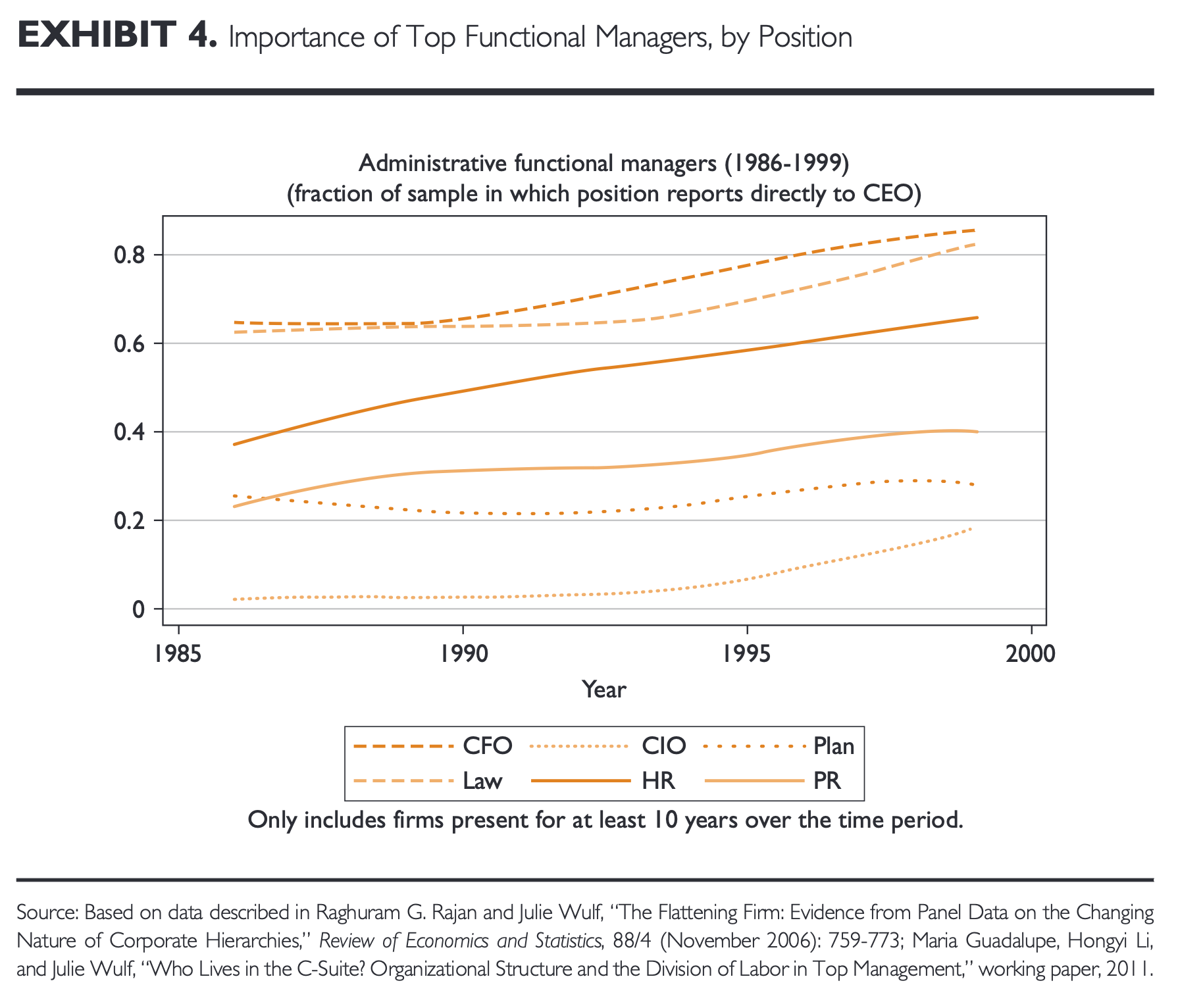

…and with quantitative rigor.

So, what can we conclude about “the flattened firm”? According to our

research, it has fewer levels and broader spans of control. Division managers are closer to the top and have more performance-based pay. However, the top team consists of more and higher-paid functional managers making corporate-wide decisions. Also, the senior executive group is led by a CEO who is more involved, not less. The flattened firm also appears to rely on more coordination among the top team and a different role for the CEO. The evidence is at odds with simply pushing decisions down. Flattening at the top is a complex phenomenon that in the end looks more like centralization. At the same time, standard classifications of “centralization” or “decentralization” are too simple to explain the flattening phenomenon. Our research shows that, in fact, firms are doing both. While our evidence is at odds with simply pushing decisions down, it seems crucial to consider different types of decisions and activities and how they vary by level in the hierarchy.

This is in line with our hypothesis on org-change discovery processes – that the most valuable question to ask is, “What decisions can you make by yourself?”

For example, division managers may “be the boss” for decisions that are closer to what customers/segments to target, what prices to charge, and what competitors to monitor. In contrast, more “staff-related” decisions around shared resources—such as managing the corporate brand, implementing a corporate-wide lean manufacturing process, or auditing and control of administrative functions such as finance, legal, and human resources—may be made at the top. To better understand these issues, it is necessary to get detailed information on decision making at different levels and across functions.

At Undercurrent, we are advocating for a different thing: pushing decision-making power out to the edges of the organization. This doesn’t happen just by cutting the marzipan layer out of the organization, but rather through a set of connected actions – adding new technical talent; creating clear lines of domain and ownership; eliminating functional management in favor of functional alignment…and some other experimental stuff that we’re still working on.

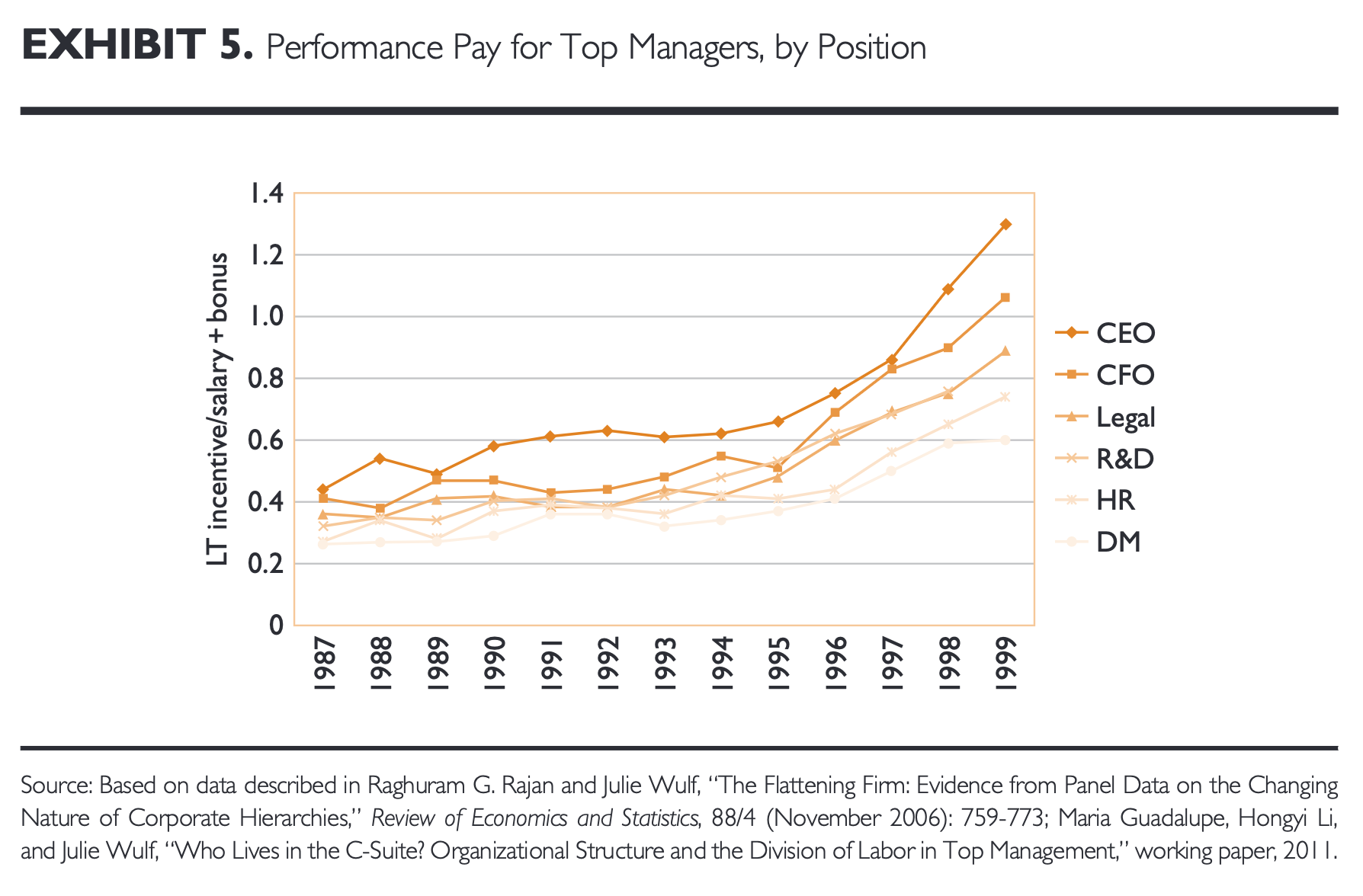

More charts, because everyone loves more charts.

Comments