How Internal Capabilities Evolve

Platform teams are an alternative to matrix orgs and siloed, repetitive SBUs.

Yesterday I wrote about how activist investors dislike matrix structures.

They're right to dislike them, especially if you take a surface view, and/or view them as one of two outcomes: we can be decentralized or centralized, and orgs swing between decentralized free-market entrepreneurship and centralized bureaucratic integration.

I think this misses the point of the matrix (as does the idea of striking a balance between SBUs and matrices with jumbo shrimp Center-Led Empowered BUs.

There's a third option: see matrixed capabilities as a waypoint on the journey toward an operating system where capabilities produce tooling for BUs to do their thing. Where the center isn't in charge but rather a set of highly specialized internal consultancies that make the organization more competitive.

I've been able to watch this journey play out in a few organizations where capabilities were created, grew into Global Functions™, and then transitioned into this Third Thing.

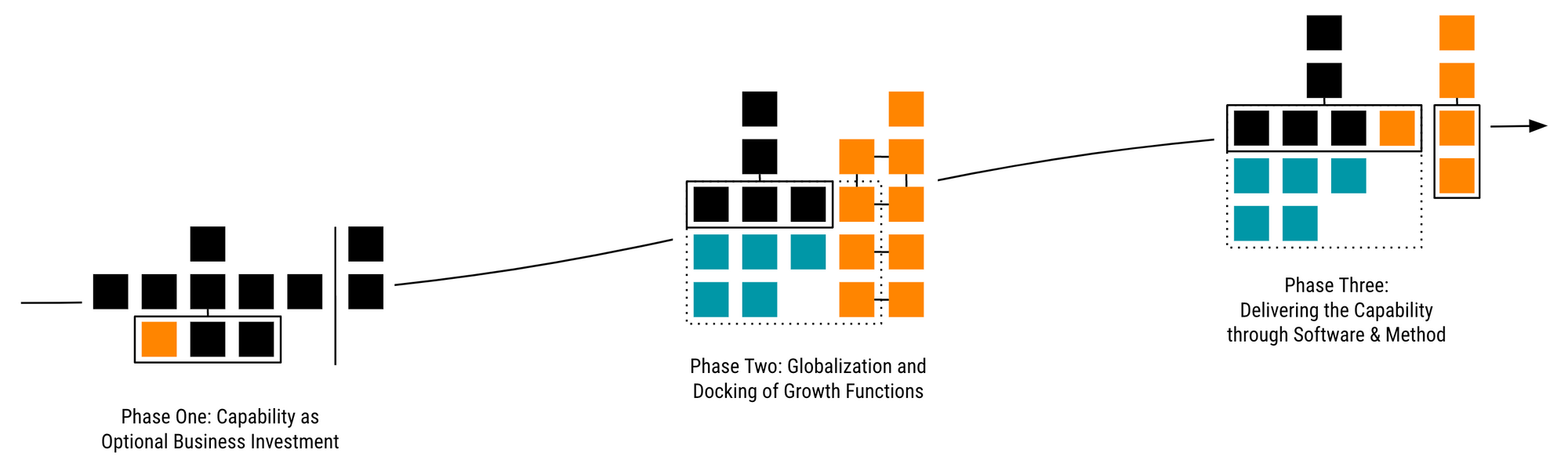

Phase One: Capabilities as Optional Business Investments

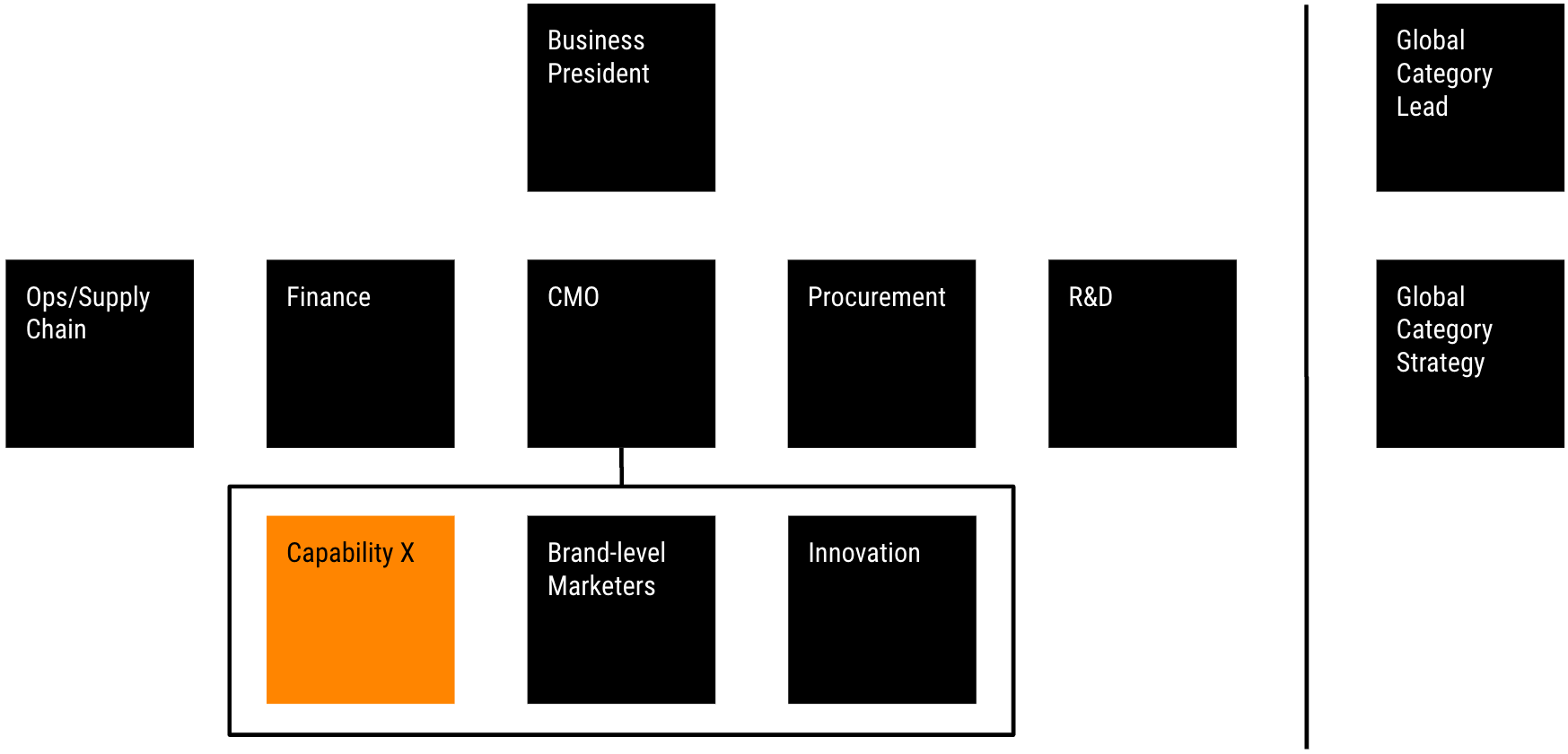

Capabilities start out as optional, ad-hoc additions to individual business units. Someone in the business notices that there's something missing that would help them compete. Someone gets hired in, or some firm gets acquired, and the new capability helps the organization perform better. This is true of all capabilities, from HR to R&D.

Chief ___ Officers (CXOs) are left to make their own calls as to the level of investment in this capability, with resource-rich global brands (which tend to require steadier, data-driven management) leading the way.

This scattershot approach leaves both intentional learning opportunities and harmonized, global brand management on the table.

Phase Two: Globalization and Docking of Growth Functions

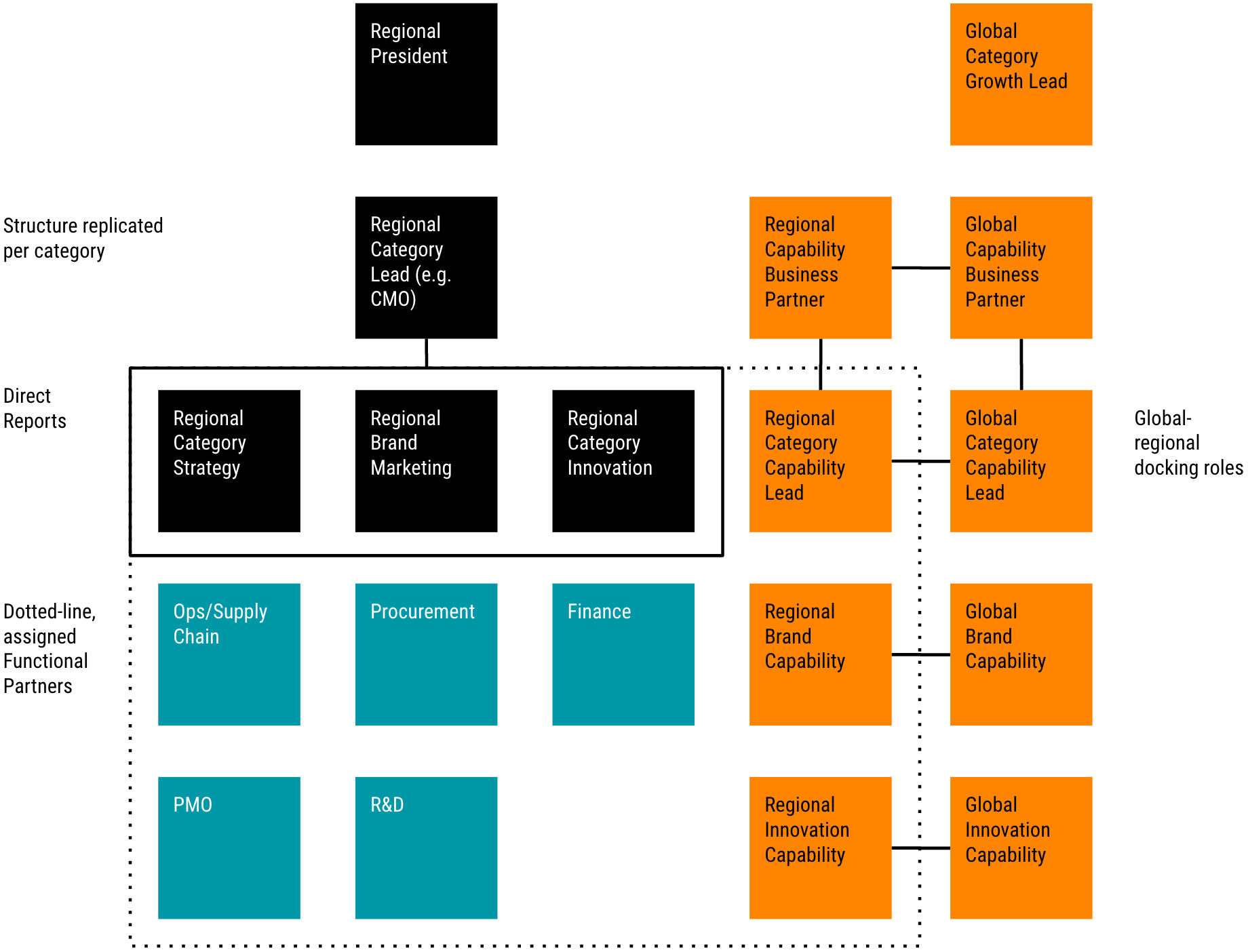

At some point, the organization gets big enough that multiple business units have this capability. The capability leads might work together, and might not. They might report into, or at least have a working relationship with a more senior person who does what they do – that person might be a Capability SVP or EVP, or a CXO in their own right. One of two things tends to happen as the business grows:

- The capability gets so important to the organization's strategy that leaders decide it needs to be done the same way in all of its businesses/locations

- The capability is being executed with such variability and duplication that customers in different areas have different experiences, and costs get out of control

So we create a global version of that function, and design some connecting points (meetings, templates, process requirements, shared incentives) between global and local.

When global/HQ management implements this three-dimensional matrix of regional, categorical, and capable consensus brings together the previously decentralized business under a common set of practices and plans.

In this orientation, the emphasis is on the capability guiding local decisions – brand, new product development, innovation, manufacturing, etc. – all under the watchful eye of global leaders focused on shared growth initiatives, platforms, or workstreams.

This is good for bringing a decentralized business together. It gives central leaders a way to enforce decisions on the edge of the org. But it's expensive to implement in a few ways.

- For one, it takes a lot of people.

- For two, it creates a heavy focus on business administration even at the cost of quality outputs or outcomes.

- For three, it tends to stifle invention in the businesses/regions, and creates conflict between the center and the edge.

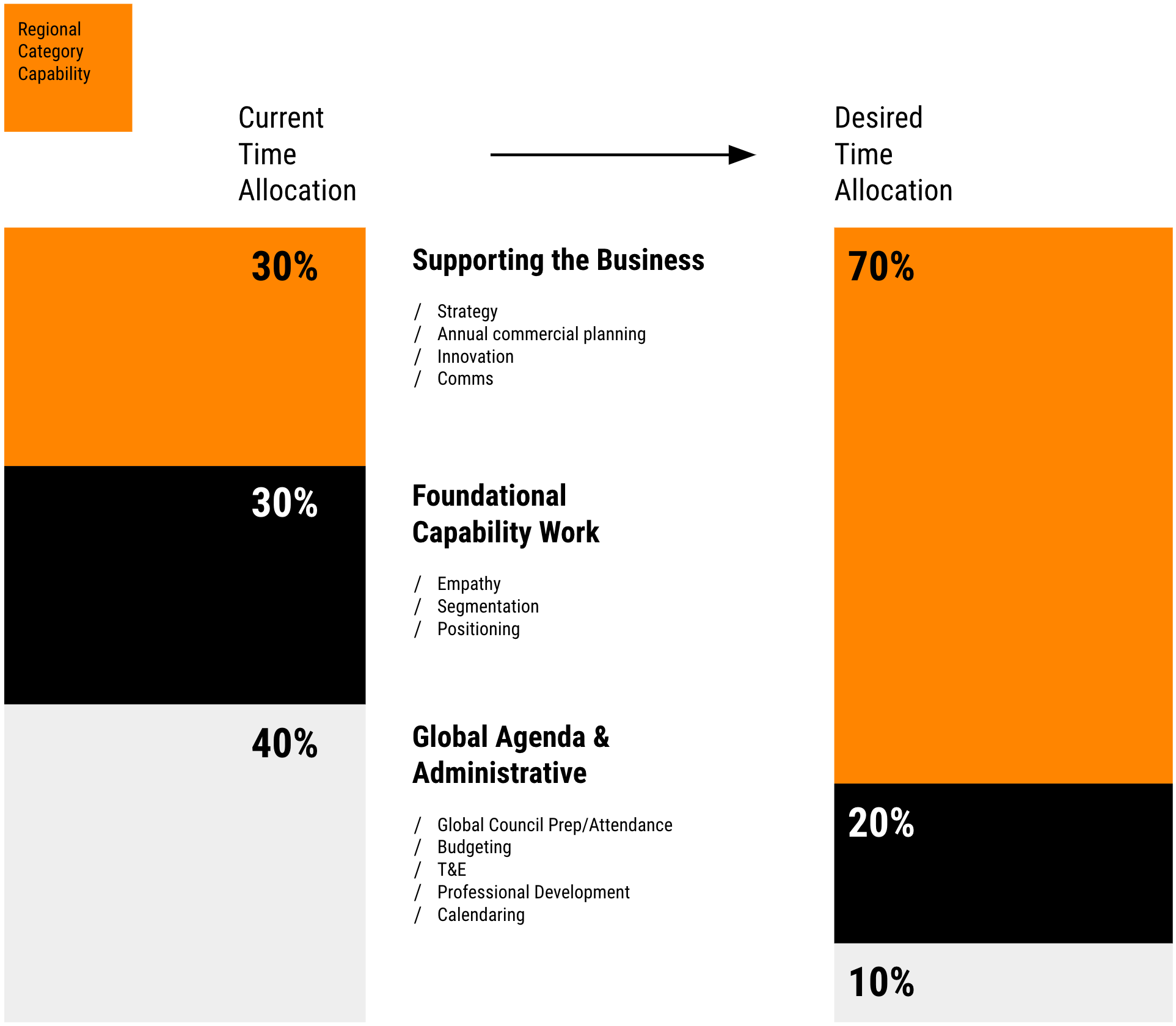

Inside the Regional Capability Team: Resource Allocation

Regardless of the actual size or composition of the matrixed capability teams – which vary both by the maturity of the local market, talent availability, and the management style of regional leadership – their key activities are common: business support; foundational or differentiated tasks that advance the capability; admin and connecting to global agendas.

Unfortunately, matrixed capability teams see their time pulled disproportionately toward non-value-adding tasks – preventing them from becoming truly integrated business partners. That sucks! It's bad for career growth and it's bad for business.

Phase Three: Delivering Capabilities through Software & Method

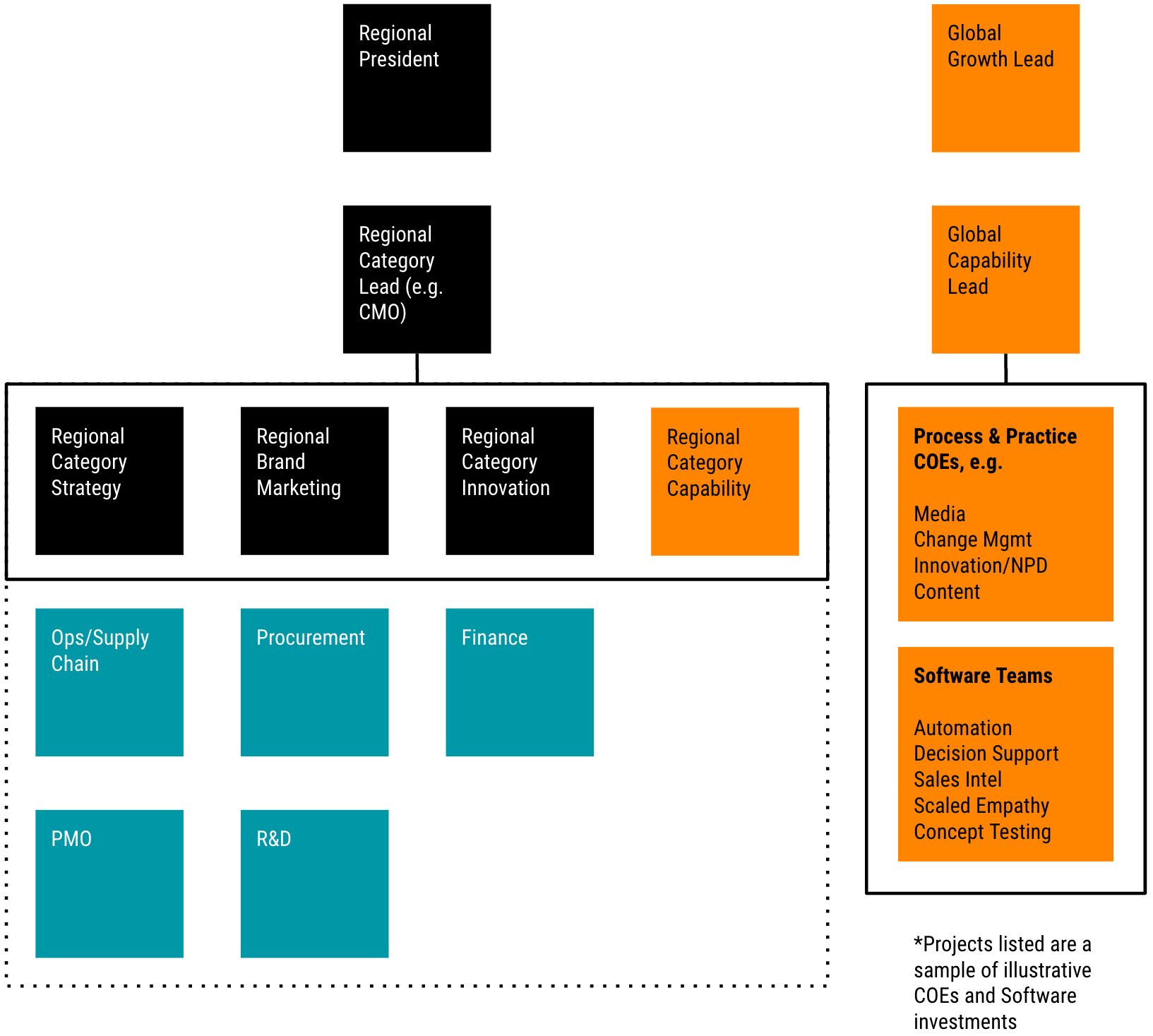

The end state for the capability in the scaled, adaptive organization is local/regional assimilation into category or brand marketing teams, supported by global/center-funded software tools, and COEs focused on scaling effective methodologies.

I think of these as "Platform Teams" – teams that build things that improve business performance. Things that raise the bar. Things that allow businesses to do things they weren't able to do before.

In this case, though, there's a mindset shift from "we control what the businesses do," to "we are out of a job if the businesses don't want to use what we made." So the skills need to change, too: the folks in those "Shared Services" probably need more of the core capability skills than they need General Management skills. They probably need to have the ability to make software-ish versions of their outputs without asking for help. They probably need to be able to sell. They probably need to be able to consult.

At the global level, the capability is probably co-located (either physically or through its tools) with other similar capabilities that support growth. These are things that tend to thrive with global support, such as R&D, Customer Strategy, Design, and eCommerce.

Comments