Netflix, Democracy, and ~Operational Excellence

Why Netflix's approach to complexity – going all the way back to 2001 – creates better results.

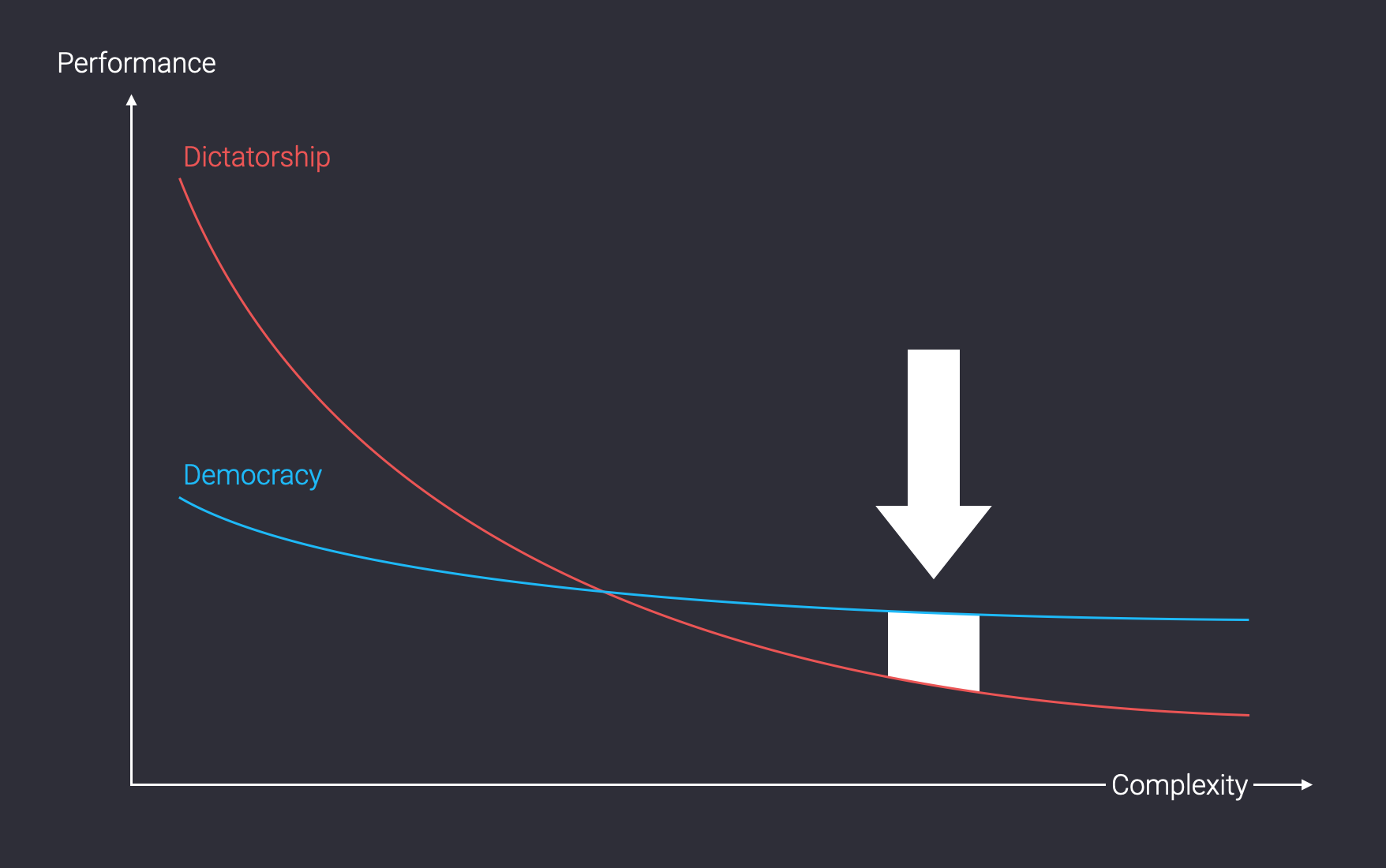

This morning, Jordan (founder of Parabol) sent me a PowerPoint slide that looked like this:

Alongside the chart was a phrase that I've now learned was apocryphal:

The reason the American Army does so well in war is because war is chaos and the American Army practices chaos on a daily basis.

So: democracy underperforms dictatorship under simple conditions. As complexity increases, democracy gains a relative advantage. (I've written about this here, here and here.)

Of course, very few organizations operate with anything close to democracy; the most common mode is something like a patchwork of dictatorships with decent trade agreements. And most versions of organizational democracy feel Kafka-esque.

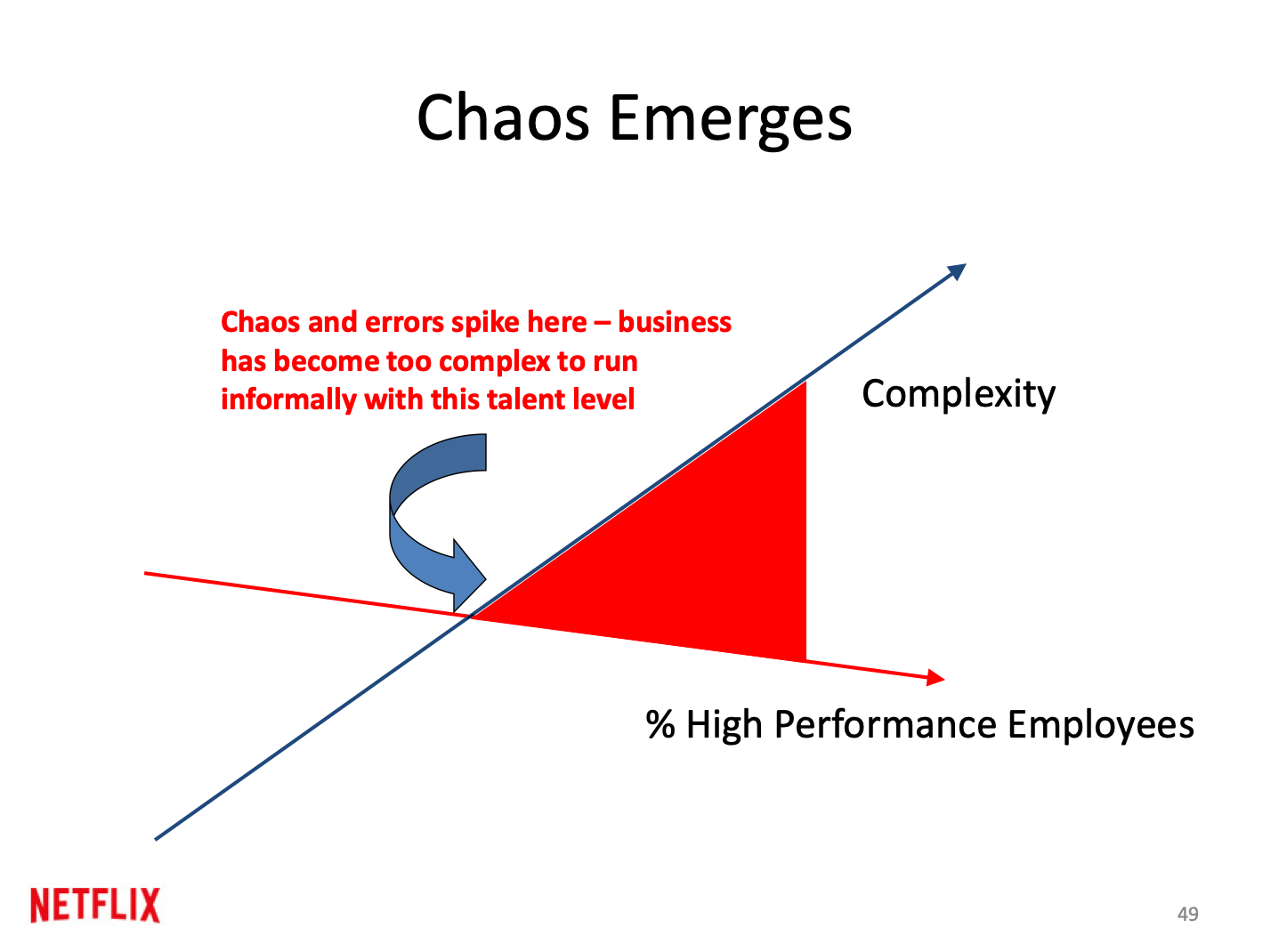

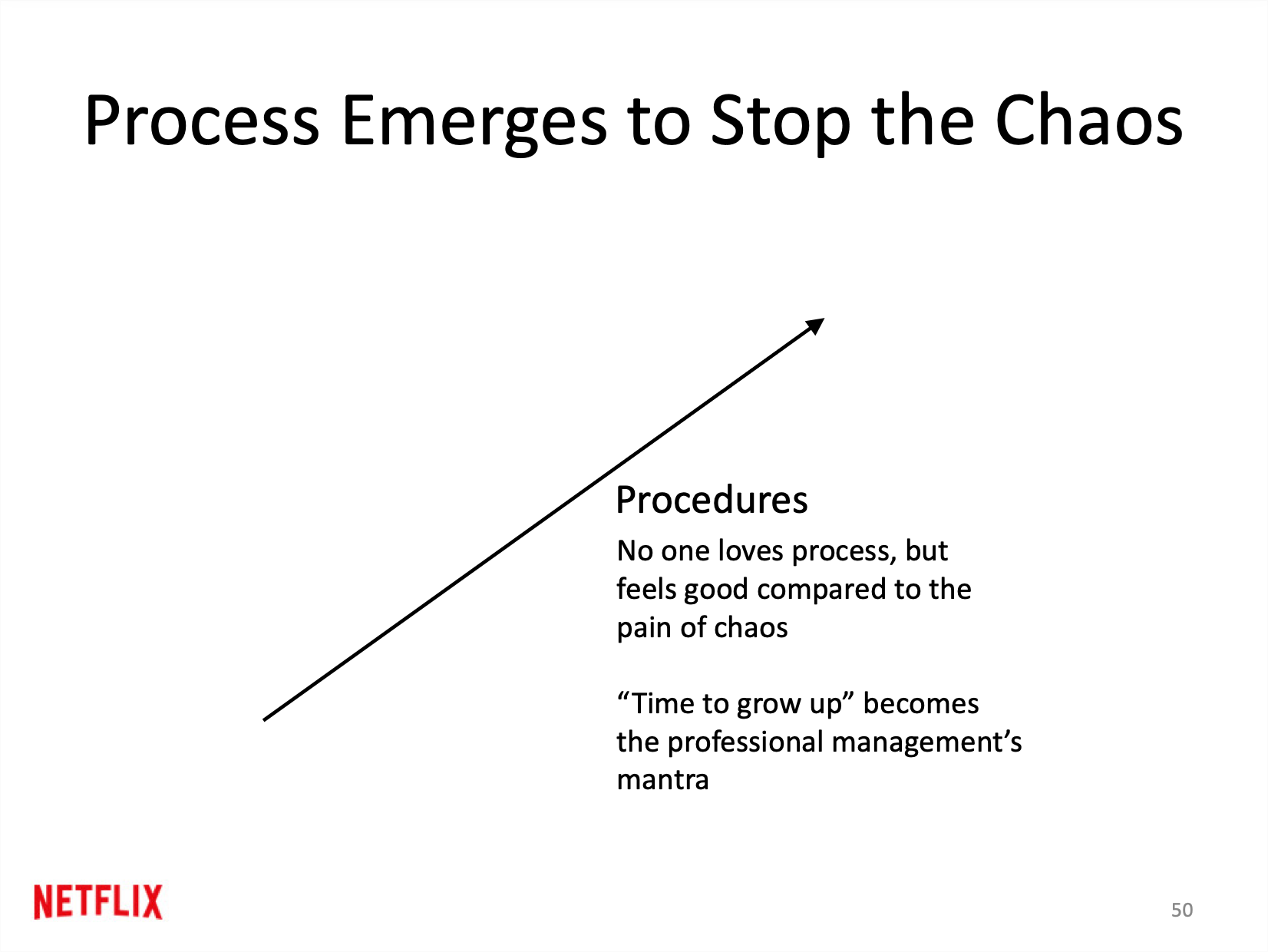

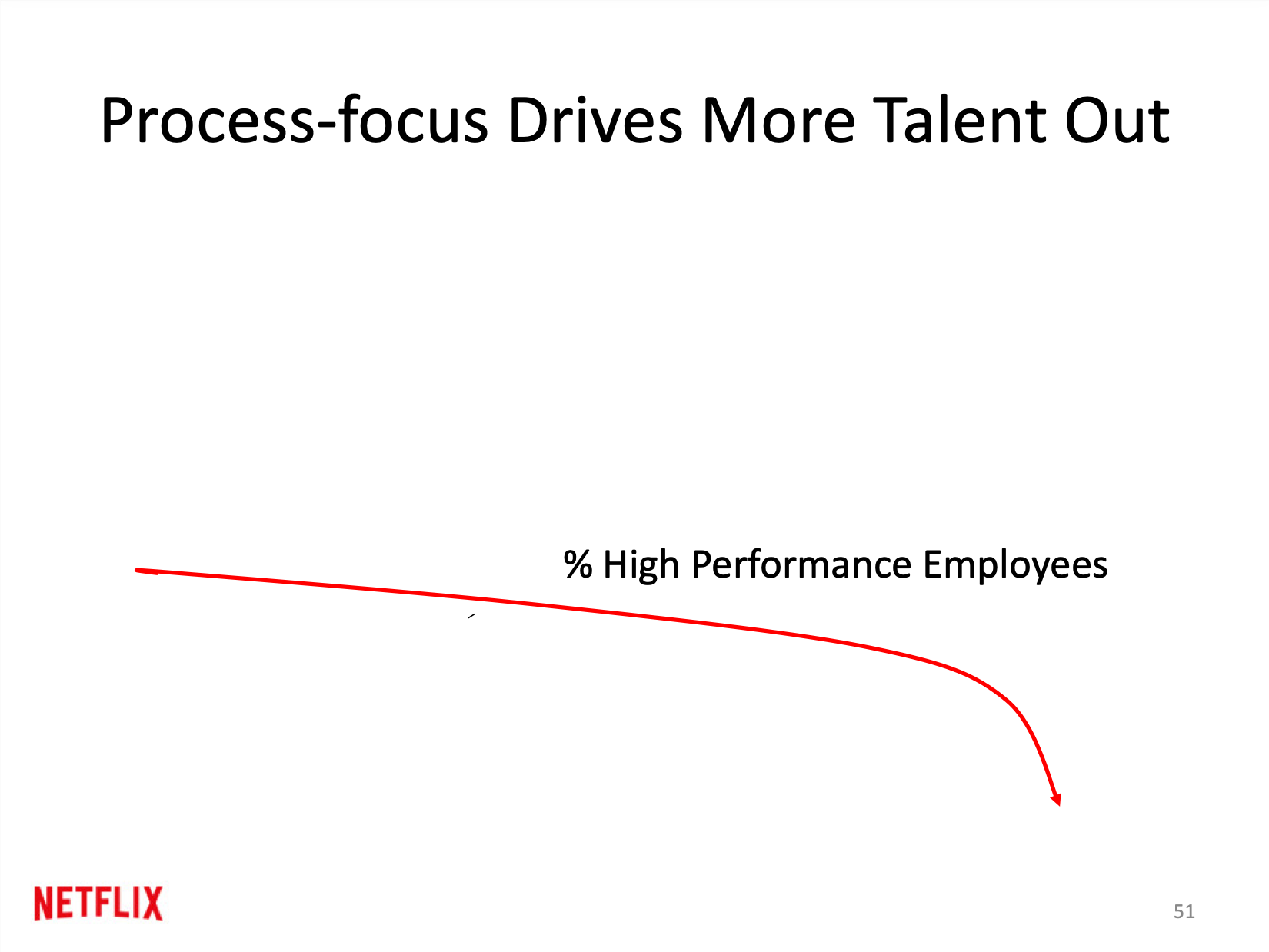

This all made me think of The Netflix Culture Deck from 2001 – specifically these three slides:

Click to enlarge.

The idea in the deck is that growth creates complexity, people put procedures in place to stop the complexity, and this drives out top performers. The alternative is to give high-performing employees the space they need to do the things they were hired to do – to help the company make better things for its customers.

I'd worried for a while that Netflix had lost its way in the Streaming Wars, but it seems like it's all good. Current reporting is that Netflix kept its culture as it scaled, and as time and turnover drifted away from that deck.

Receipts? Check out this description of Netflix culture on Hacker News, inspired by Stratechery's Netflix's New Chapter, and intended to explain this phenomenon of Netflix's culture and Reed Hastings: "To say that Hastings excelled at execution is a dramatic understatement; indeed, the speed with which the company rolled out its advertising product in 2022...is a testament that Hastings’ imprint on the company’s ability to execute remains."

I particularly love this bit:

We kept hiring great engineers and saying "if we do it this way it will be a better experience for the customers" and for us internal teams, our customers were other engineers, so we made the best internal tools we could to enable developers.

Such an underrated mindset.

PS: the "Netflix's New Chapter" article is an instant classic.

Experience Curves & Rising Complexity

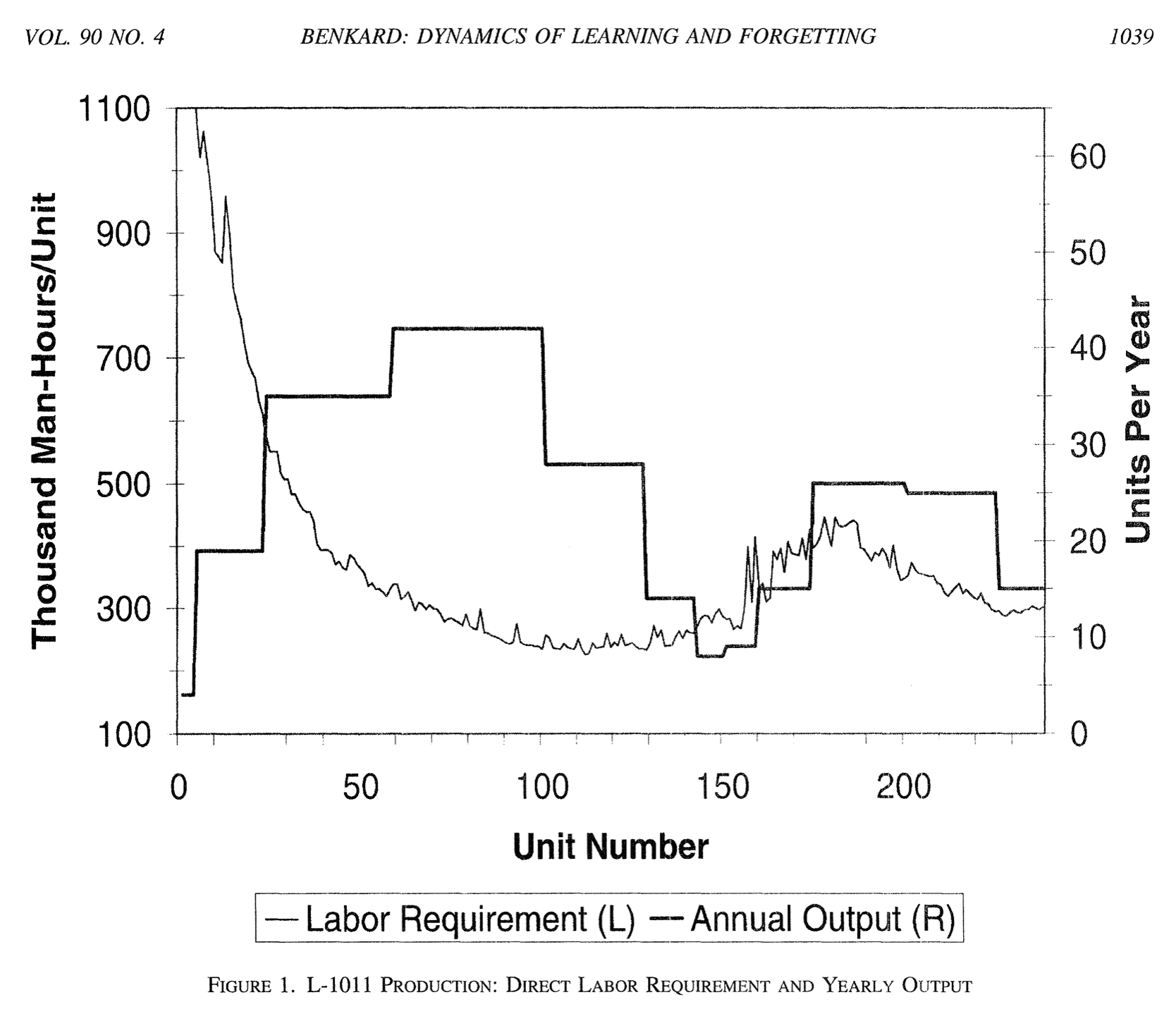

Switching gears for a moment, there's a phenomenon in manufacturing called the Experience Curve. The idea is that with each new unit you produce, the labor unit cost for the next one you make will be lower. Because of learning, process improvements, growth in individual laborer skill, etc.

(That bump at the end is from another thing that I should write about another time – how organizations "forget" through turnover.)

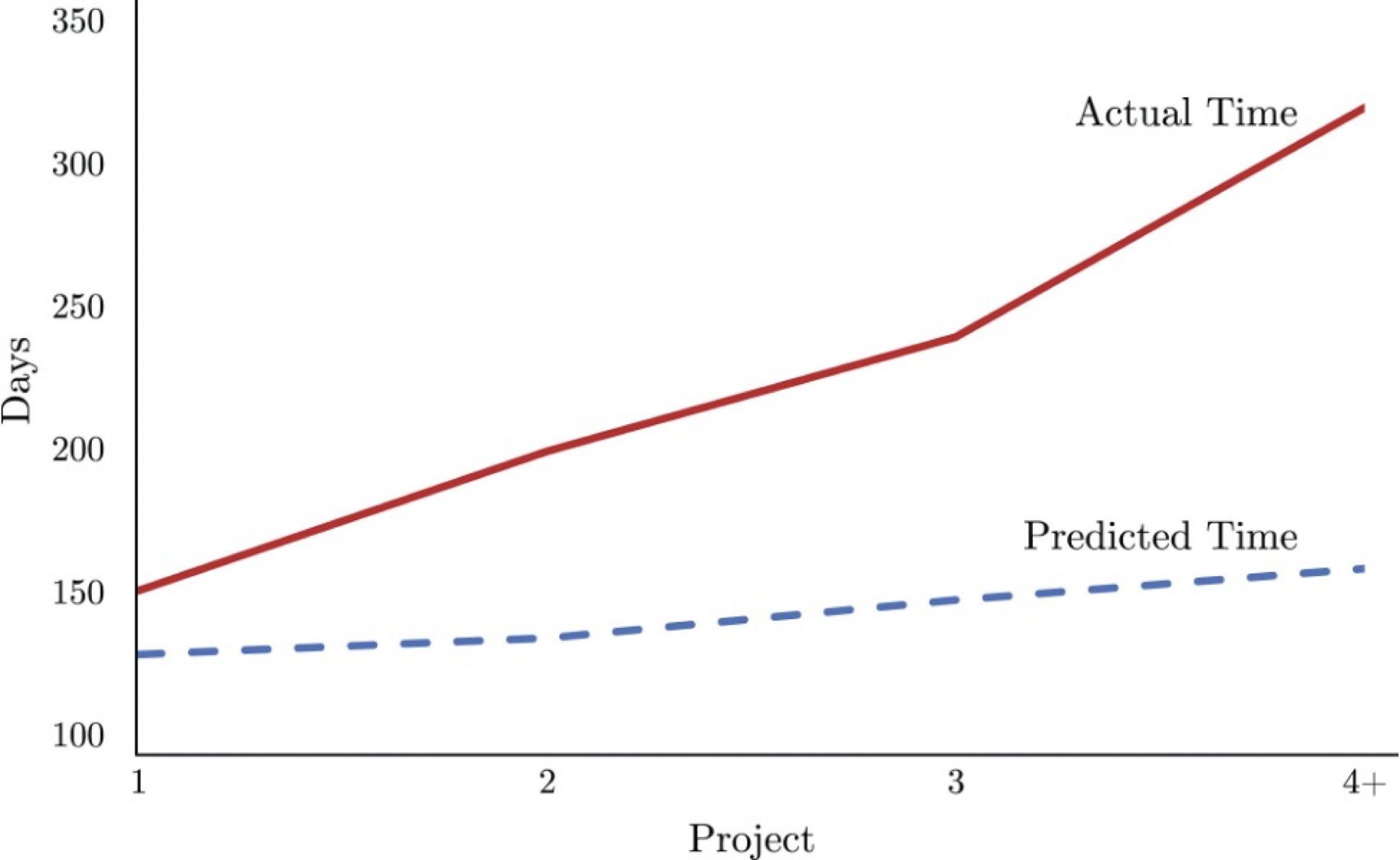

But then there's this recent research highlighted by Ethan Mollick that looks at the entrepreneurial version of similar measures. What happens to successful entrepreneurs when they move on to a second, third, or fourth project? They add complexity to their offer, and their time-to-deliver goes up.

Launching new things like, say "streaming movies over the internet" or "adding advertising to a subscription-based service" isn't the same thing as "produce an incremental L-1011."

Why democratic organizations fare better

Democratic organizations fare better than autocratic ones for at least two reasons:

- They're more efficient learning machines

- They teach more of their people more about "the business"

Learning: Organization-level learning can happen through things like metrics and dashboards, of course, but the stickiest version of it happens when leaders listen to teams, and teams listen to each other. Quoting from Jedberg again:

When some of the engineers said, "we could do this a lot faster and eventually worldwide if we hitch our wagon to this new AWS thing". And so management got out of the way and said "if that's what you think is best, we will support that".

Listener, that's psychological safety. Imagine if the leaders had said, "Nah, Reed is better friends with Bill, so we're going to use Azure." The engineers would stop speaking up, they'd probably quit, doom spiral, etc.

Teaching: When leaders are focused on providing robust context for decisions, rather than simple mandates, individual contributors (who are usually but not always less experienced than leadership) learn more about the fundamentals of the business.

How do we make money? How do we decide? What does the board care about? What behaviors are encouraged? What are the implications of choosing technology X? What happens when we change our process?

I've seen this firsthand. When we swapped over to self-management at Undercurrent in 2013-2014, we were forced to start teaching everyone about our approaches to finance, resourcing, project selection, scopewriting, escalations, pricing, conflict management, etc. Before that shift, we'd often answer questions about these topics with something like, "don't worry about that, focus on your craft." That was no longer acceptable, nor good business practice.

Mental overhead for everyone shot up.* Back to the slide at the top: our normal operating mode was more chaotic, as policies, practices, and teams were liable to change at a moment's notice. But after the all the core business teaching happened – and not all from "leadership" – we were much more effective.

*Anecdotal, but if you were there, I'm sure you feel me

Comments