The Cook’s Economist: Functional Publishing Models

Examining the ways in which structure changes what gets published, and why

Two years ago at our Web2.0Expo talk, Alex and I posed the following question:

It’s still a worthwhile question, especially when companies can answer, “Zero, actually” and be taken seriously. And oddly enough, two companies that are in the magazine publishing industry are able to answer the question with confidence. They’re not startups, but like many in the digital world, they aim to monetize content.

“The Economist” is a trite answer to a separate question – “Who’s killing it with content?” – but it’s worth noting that their $130 annual subscription ends up in the hands of only around 1.5 million people. In spite of that relatively small number, the newspaper makes money. £60MM every year. And that figure is growing.

Cook’s Illustrated is a less-cited example, but they continue to impress. They’re private, so they’re not quite as easy to assess as a business, but they seem to be growing, making money off a model that doesn’t include advertising, and experimenting effectively in the digital space. They publish 6 issues each year, do not discount their subscription rates, and charge for the digital version even if you get the magazine in the mail. And remarkably, somewhere near 80% of their one million subscribers re-up annually. Gangster.

But beyond their business success (the most important metric in my book), my case for them being awesome, effective publishers of content worth emulating by brands and other folks in the content game revolves around three key things:

- They’re committed to a unique, obsessive perspective, and everything they make flows from there

- They’re using digital channels in effective ways to drive people toward their moneymaker

- As far as I can tell, they’re organized around efficient content creation

Obsessive perspective

Cook’s is famously obsessive. Its founder Christopher Kimball believes there’s a single right way to do things, and the magazine feels like it grows from that perspective, rather than one that’s about a love of food. Which to me is a good thing. There are probably thousands of places you can go to express or indulge your love for food, and I’d argue fewer than a handful that really scratch the perfection/process itch. Being obsessive and having an uncommonly held position allows you to be different, to compete with fewer people, and unlocks the ability to thrive off scarcity. I’ll pay for Cook’s because there are no good, free substitutes. And because I want Cook’s to continue to to exist.

Importantly, the perfection “thing” extends to how they make their core, stock content:

“Kimball’s idea is simple. So simple that he’s amazed it’s not how every publisher does it. The reason the others don’t is because it’s crazy expensive. Every recipe that appears in his publications and on his TV shows must represent the single best way to make a dish — and they are forged in the fires of the Mother of All Test Kitchens.

“The Cook’s Illustrated recipes follow the most rigorous journey. First, each recipe idea is pre-surveyed to see if readers are even interested in it. Then, based on research in the company’s cookbook library, a test-kitchen cook comes up with several versions of the dish and submits them to a staff taste test. She is then pummeled with questions about why she didn’t try this ingredient or that sauteing method or a different type of sugar. She goes back to the kitchen for more experimentation, and more critiques follow. Only when all hands believe the recipe is the best it can be is it sent to a handful of readers, who make it and report whether they’d make it again. If a recipe – even after all that time and testing, and even after more revisions – doesn’t score well with the readers, it ends up on the kitchen floor. Surviving recipes are published with the story of their journey in the test kitchen. There’s even a science guy on call to conduct more technically challenging experiments and add explanation to the articles so readers can learn why, say, on a molecular level, cream of tartar does what it does (and I have no idea what that is, but it is apparently very important).”

– Perfection, Inc. Boston Globe, 2009

Content as advertising

The success of Cook’s and its parent America’s Test Kitchen as money-making products/services subsidizes the creation of content and the support of channels, which effectively operate as marketing for the paid channels. And because they’re organized around making content and have been for some time, they’re much more likely to be successful at making content for the internet than other similar organizations.

For example…

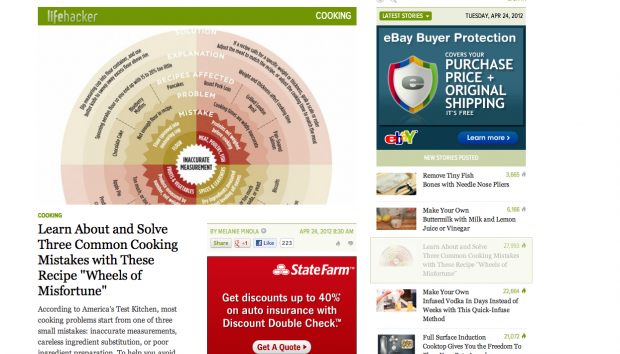

A diagnostic infographic found its way to Lifehacker…

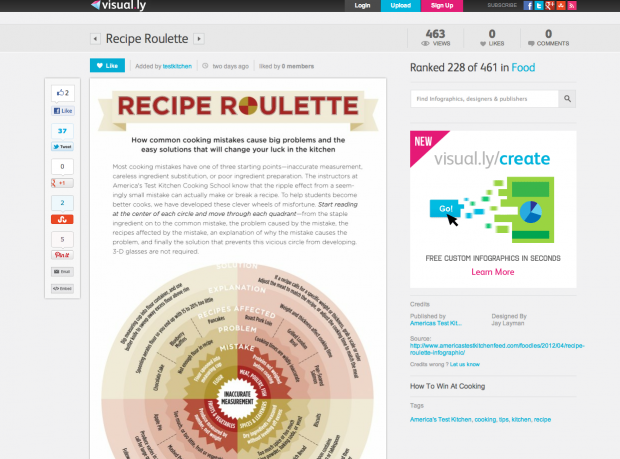

I clicked and found out that it was from America’s Test Kitchen, and Lifehacker linked to their visual.ly page…

Where they’ve posted this and a couple more infographics, including this one about cakes throughout history. The profile links back to what looks like a new digital property, “Feed”…

And it’s a site that offers Cook’s-like instructions and recipes, though certainly not in the same, incredibly analytical, detailed and sometimes obnoxiously complicated style as the magazine. It also provides a view behind the curtain at the Test Kitchen, and provides individual authors not only a byline, but fully developed pages that they might use to grow their personal brands.

This is a significant strategic move, but it’s one that feels sustainable. It doesn’t appear that there are new staff members that are expressly dedicated to the new site: instead, it seems that the site is populated by content generated by more junior/digitally savvy staffers of ATK. And if they’re going to blog about food anyway – because they’re people who love food and love the internet – why not give them a brand-positive place to put it? Your content costs are effectively zero (nobody new to hire, small negative changes in productivity, perhaps), and your brand spreads through the efforts of many. Makes sense to me. Get your flow for cheap.

This only works if you’re organized for creation

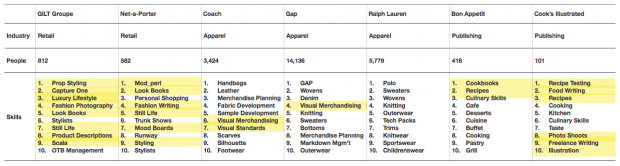

So this is fascinating. I did a little poking around on LinkedIn to see how a few different organizations are structured. I had a hunch that companies that do better at the internet have more people making shit for it.

I’ve listed GILT, Net-A-Porter, Coach, Gap, Ralph Lauren, Bon Appetít, and Cook’s Illustrated, and I used the “insightful statistics” section of LinkedIn to pull the top ten most common skills of employees at each of the companies. Highlighted in the image above are skills that in my estimation relate to content creation. Compare GILT and Net-A-Porter to their suppliers/rivals/supplier-rivals. Do the same for Cook’s versus Bon Appetit. Granted, these are self-reported skills. And they’re not comprehensive. And each of these companies makes money in a different way.

But on the internet, competing for attention, they’re all being judged the same way. And the companies with more content-creation skills are winning.

So if you want to compete on the internet, up your skills. Hire people that can make content, not just people that know how to pay for content. Easy, right?

So, content makers, get to it.

Comments