The Organization Is Broken

Are organizations degrading the human experience, or are they poised to accelerate our progress toward dignity and achievement in the 21st century? Yes.

Organizations are our only hope. They’re also completely broken. Let’s not settle for boring, ineffective, inhumane working lives. Right? Right. Read on.

Where we went wrong

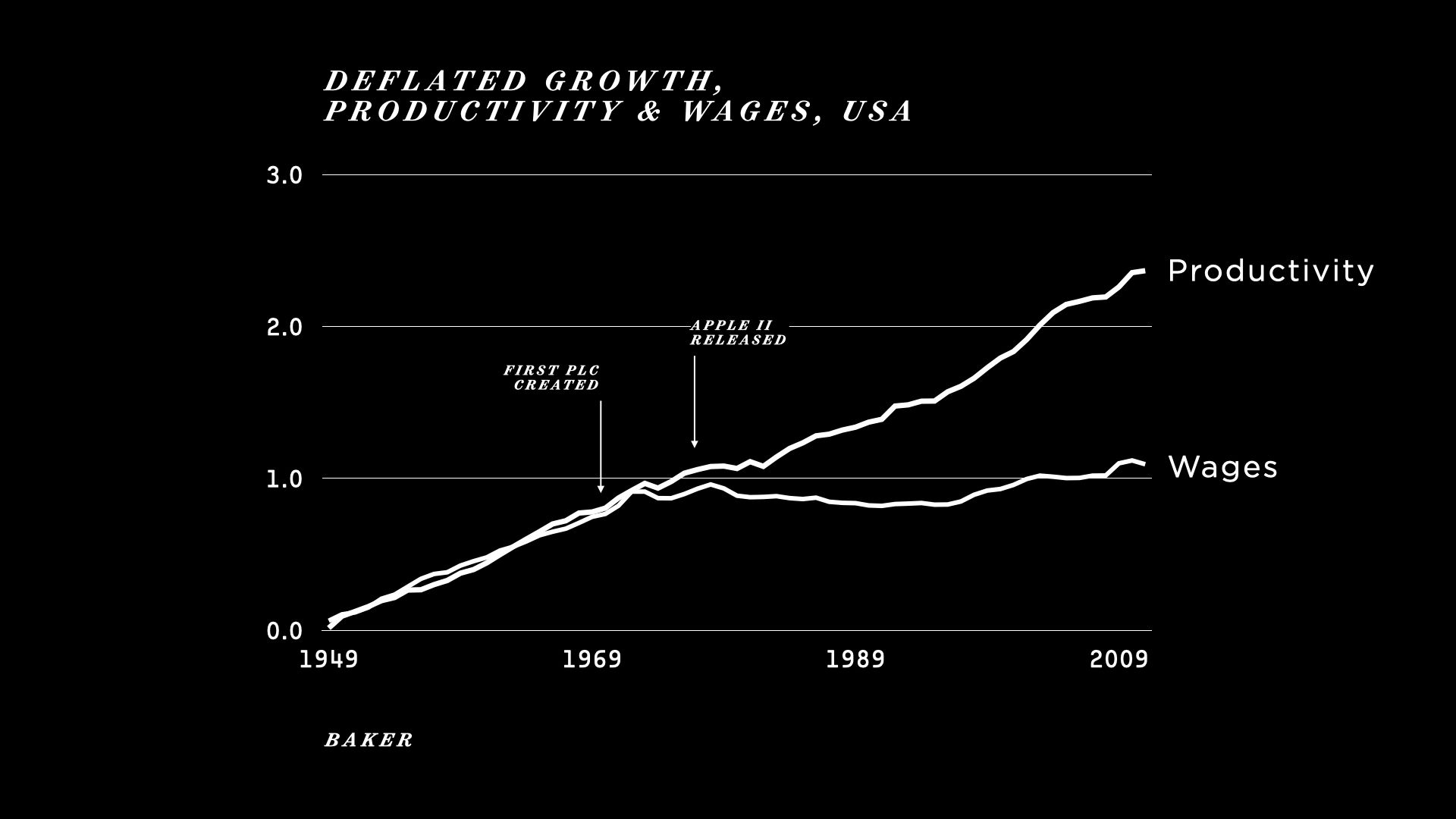

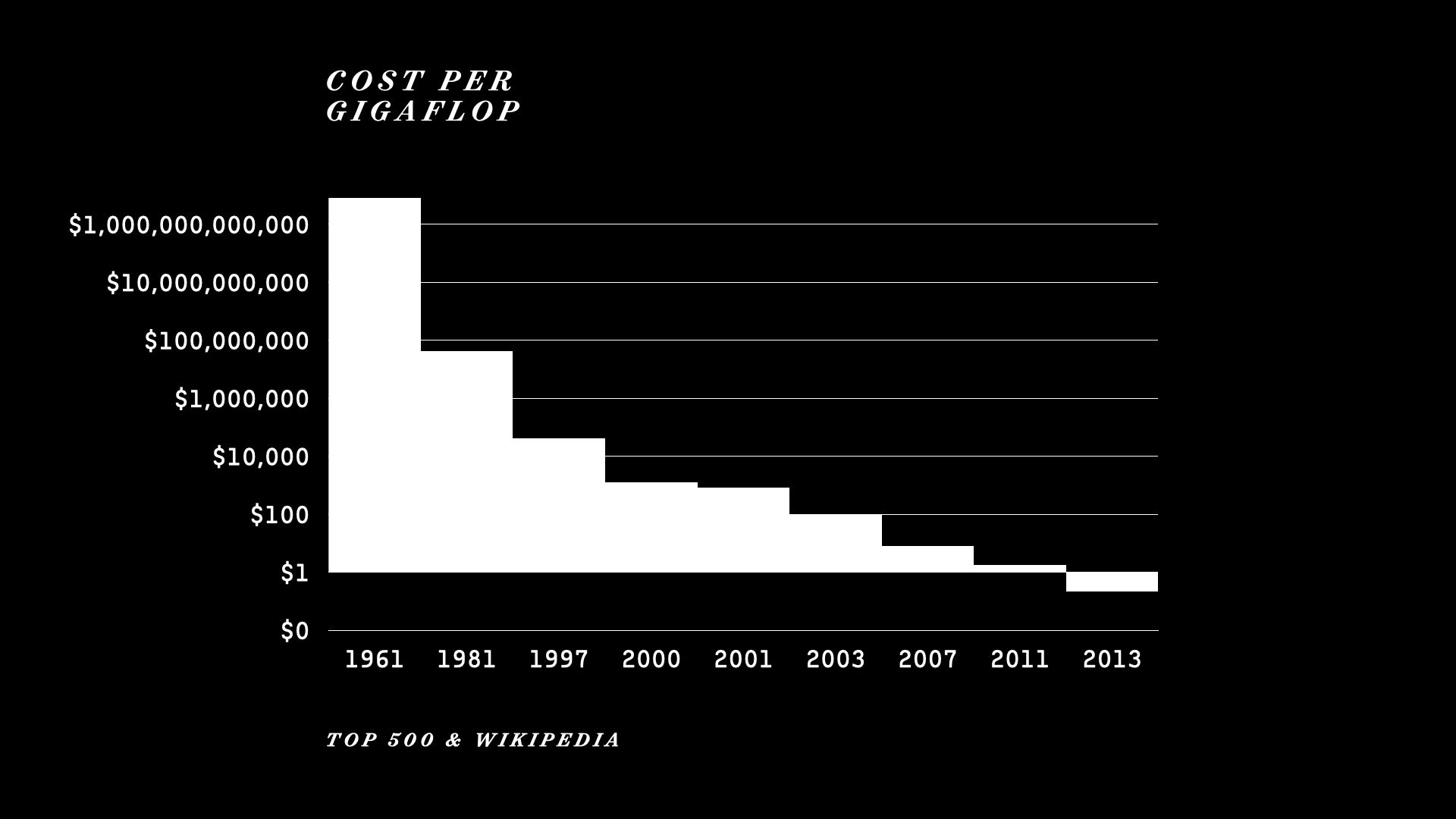

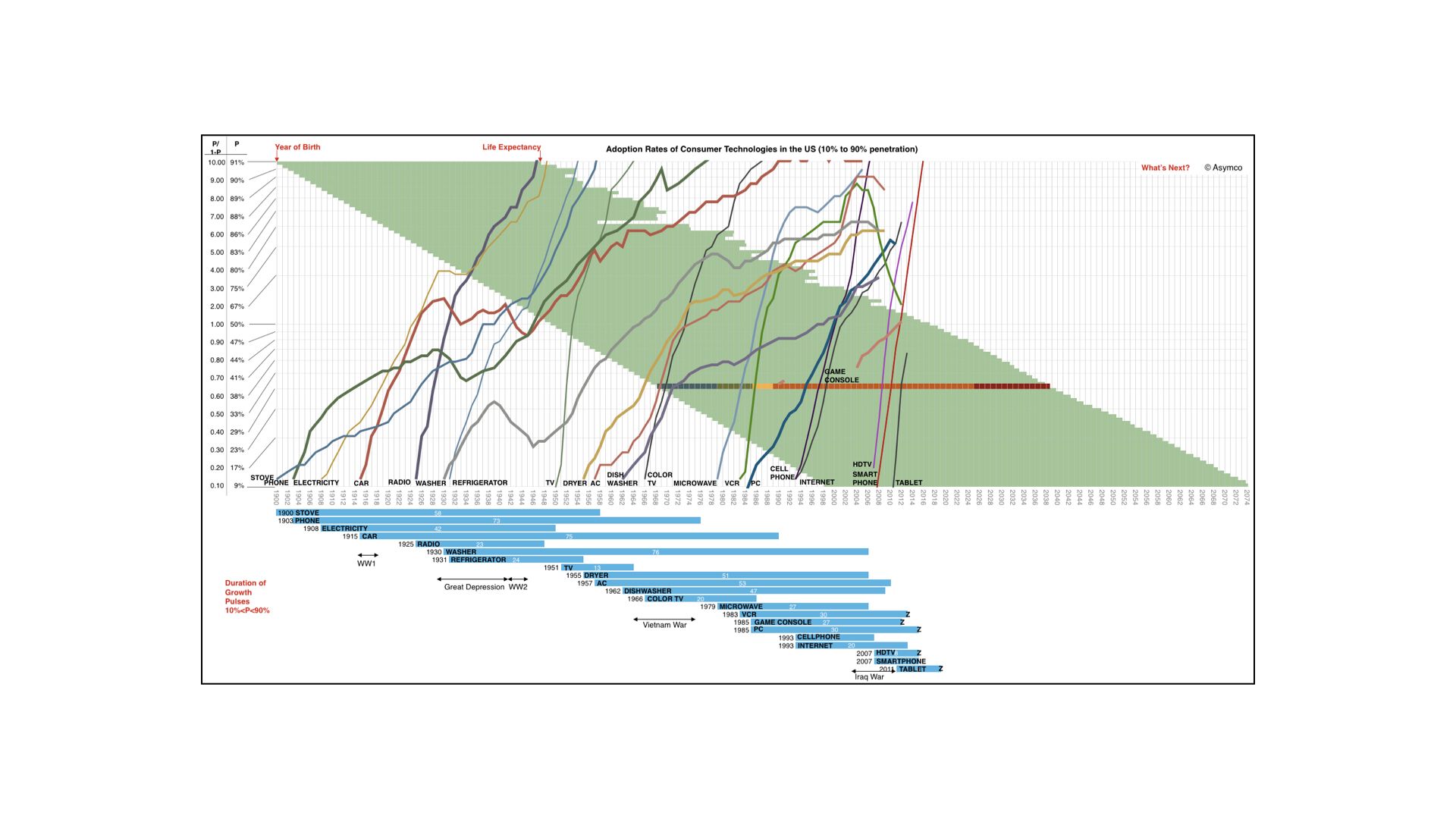

Since the early-mid ’70s, wages and productivity — when measured in terms of widgets produced per hour — have been diverging. Wages are generally flat, while workers are close to 2x as productive today as they were 30–40 years ago. This divergence is coincident with the start of the so-called “Third Industrial Revolution,” marked by the introduction of the Programmable Logic Controller (1969), allowing factory-owners to install ever-more-capable robotic production equipment. Things really started to get interesting with the commercialization of the personal computer and the advent of the supercomputer (1976-forward), allowing white-collar work to feel the impact of Moore’s law.

But if you’re a worker, being paid wages, productivity gains alongside flat earnings aren’t so much fun, even if you have what used to be millions of dollars of computing power in your pocket.

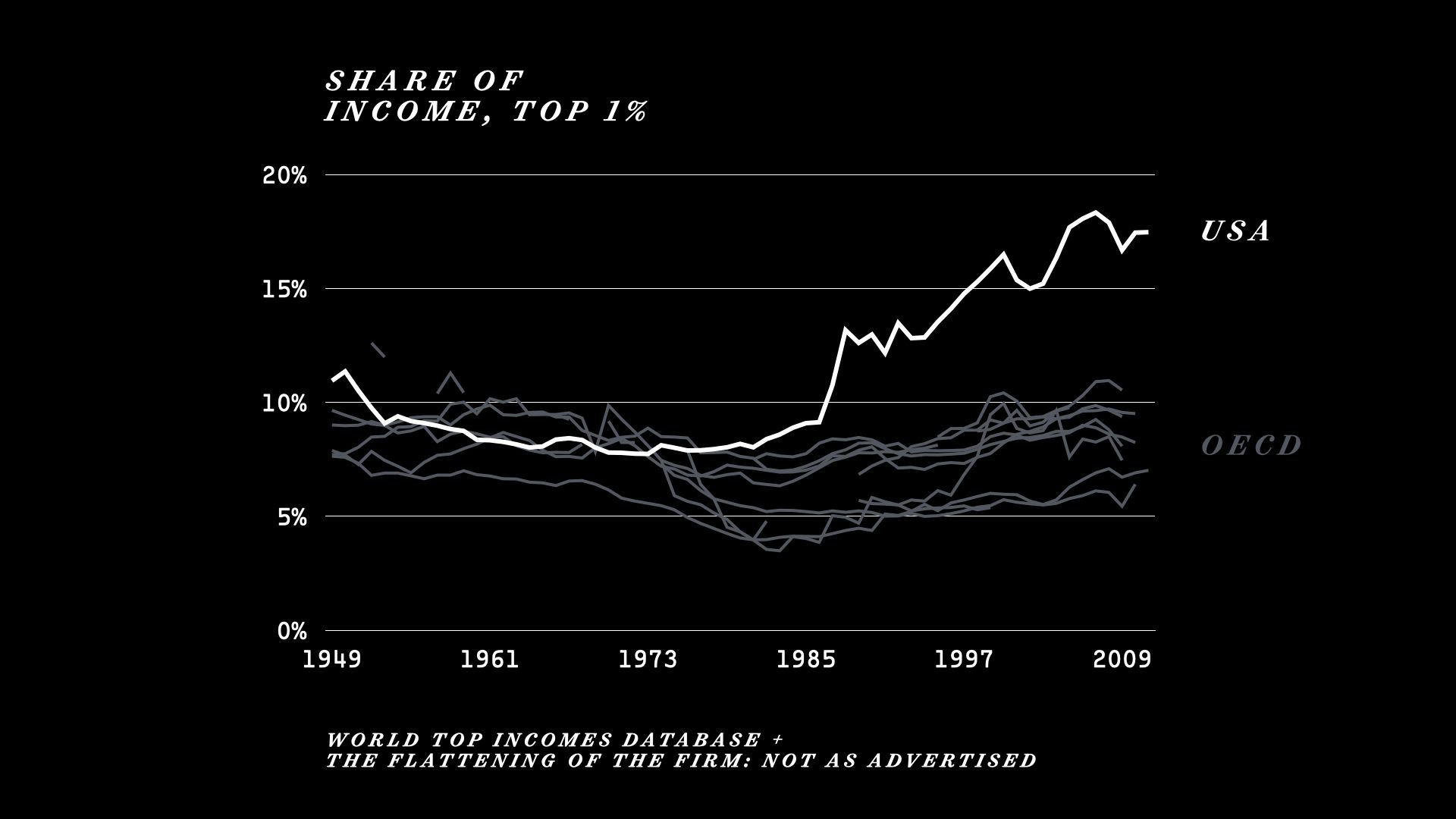

When you compare this chart with the first one — same date range — it’s clear that someone is profiting from this change. While wages haven’t changed much in the last several decades, the portion of income going to the top 1% of households has.

When comparing the US to other industrialized countries, it’s clear that our organizations reflect a choice: to line the pockets of capital owners, while leaving everyone else out in the cold.

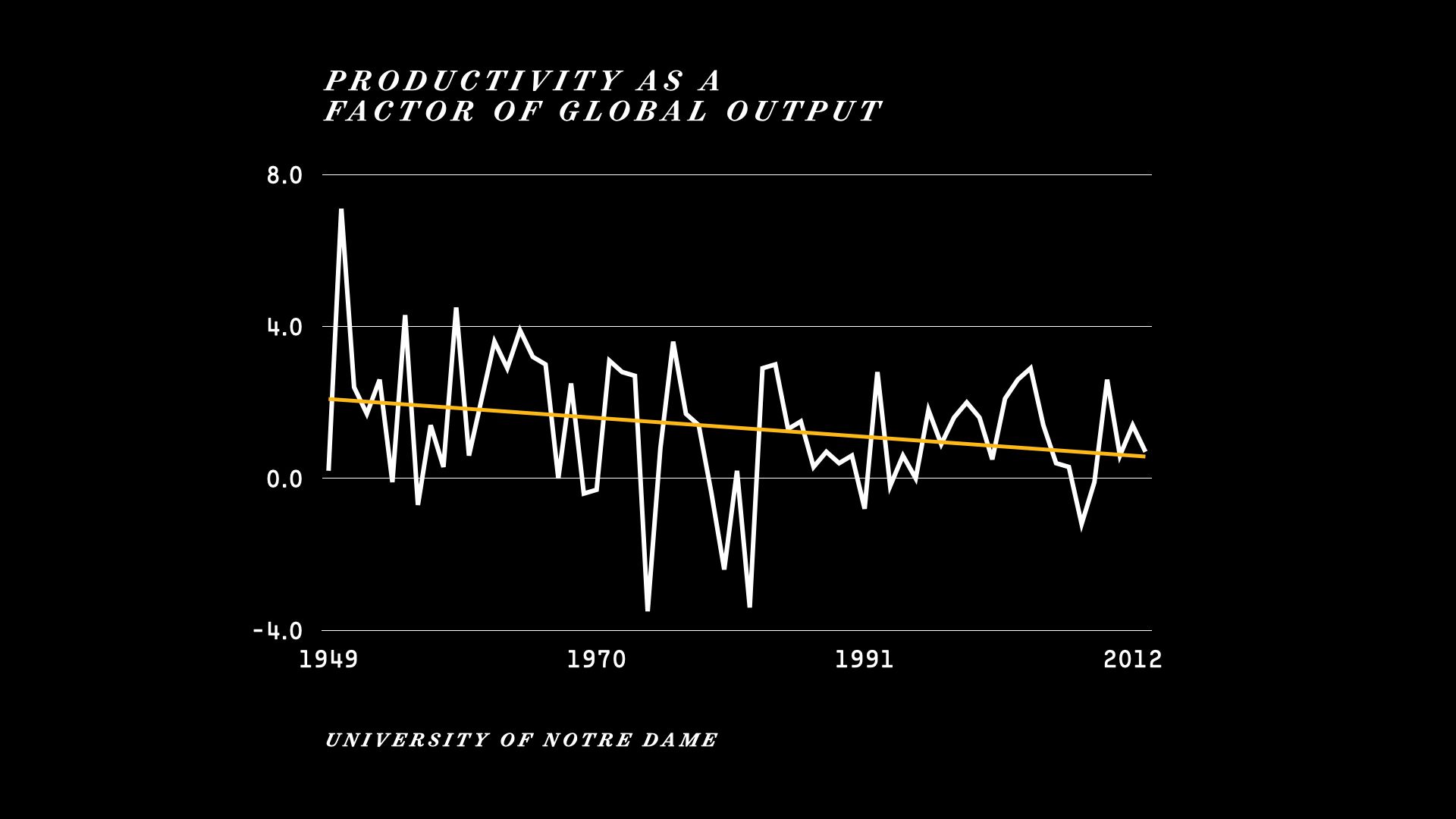

Even for the owners of capital, the news about “productivity” hasn’t been entirely positive. There are (at least) two ways to measure productivity: the first, used on slide 2, is fairly straightforward, counting the output of labor per hour worked; the second is perhaps a bit more mysterious, and is defined as the portion of output not accounted for by production inputs. Economies and organizations all have measurable output, and this output is understood to be created by capital and labor inputs. But when you compare these factors of productivity and the total output for the entity, there’s usually an unexplained difference.

This difference — the total factor productivity — has been declining for some time. So while there are productivity winners and losers, globally we’re better off investing in capital instead of labor or productivity.

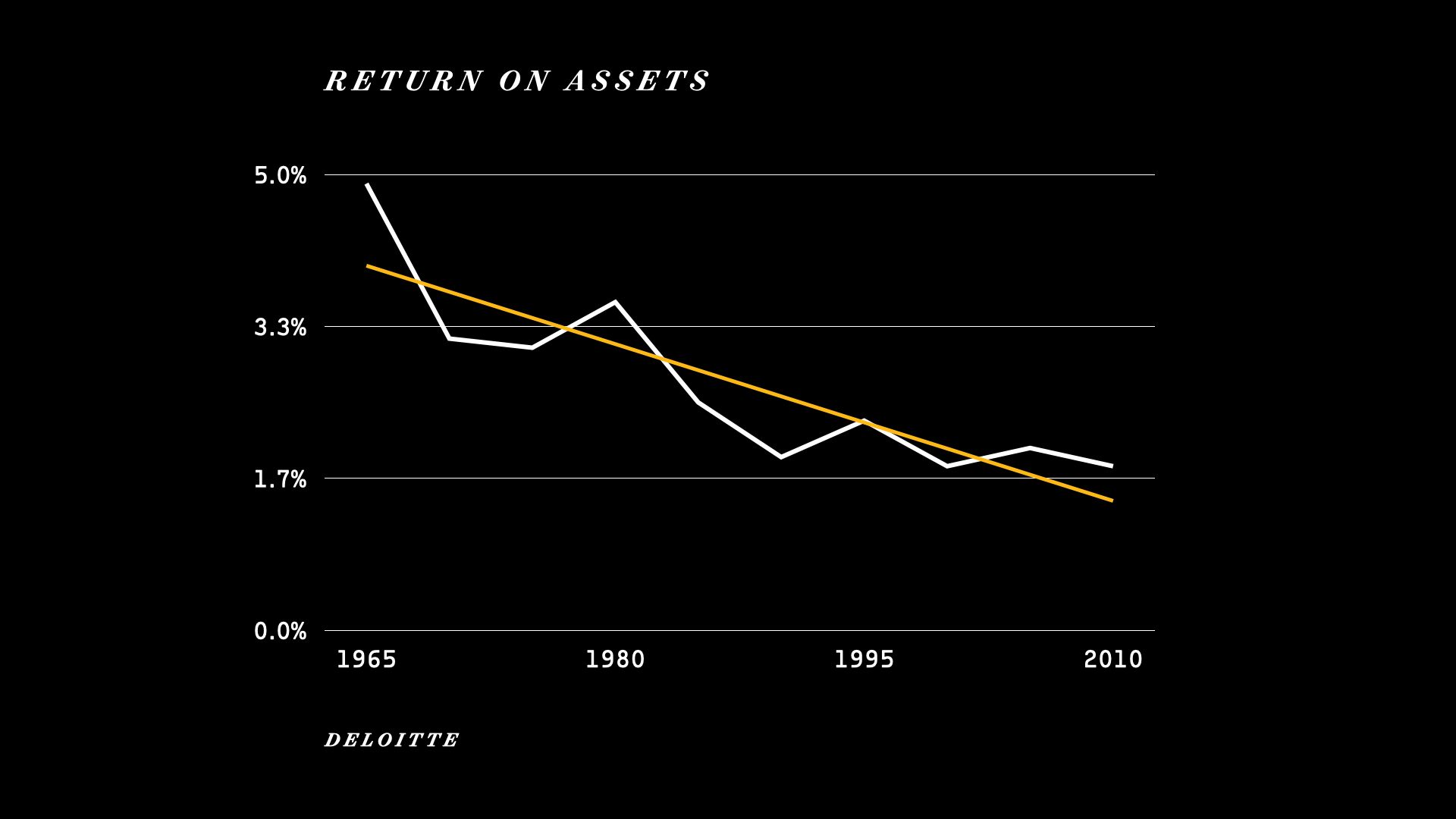

Even as the fat cats’ wallets get fatter, their organizations do less with their assets today than they have in the last 40 years. Again, with companies like these, it’s better to invest in capital markets than on building a legendary organization.

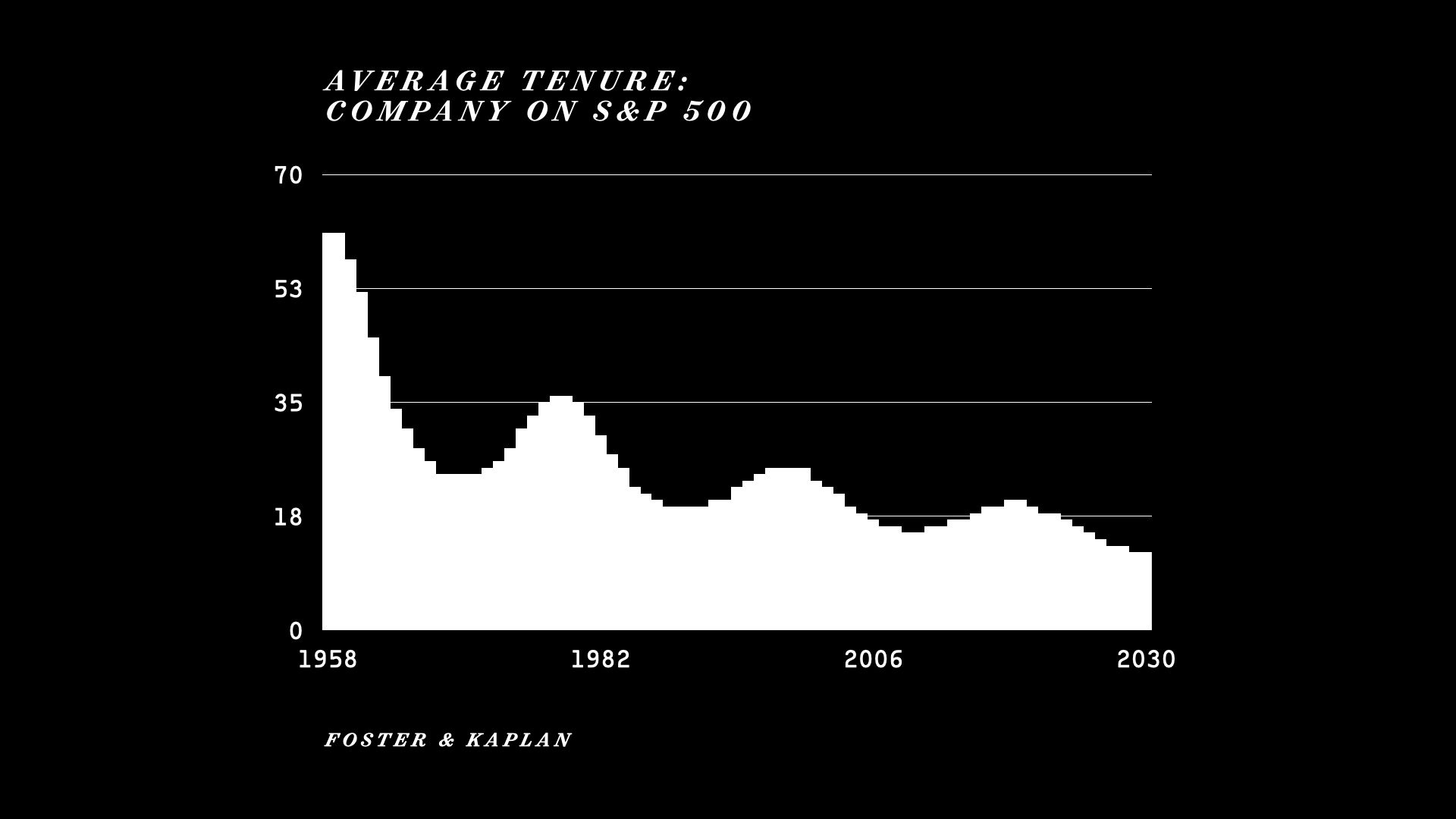

Coincident with all of this, organizations’ environmental context has become more dangerous. In the 50s, a company on the S&P 500 could expect to live 60+ years — well into wizened maturity. Today, the life expectancy for these large, important organizations is only 14 years. Companies aren’t people, and it’s a good thing — you’d have to go back millennia to find such inhospitable conditions.

This is a too-frequently cited trend, but it’s palpable in the hallways of Corporate America. In this economic context, making mistakes isn’t tolerable, particularly for managers and line employees. CEOs and execs can float from job to job — handsomely compensated along the way — while those in the middle and at the edge suffer the consequences.

This culture of fear permeates all the way to update meetings and BCC fields, where CYA is more important than ROI. And this makes a certain amount of sense: if you’ve got a mortgage (or two) and a kid (or two) in private schools, and are saving as little as your peers, a single mistake can have decades-long repercussions.

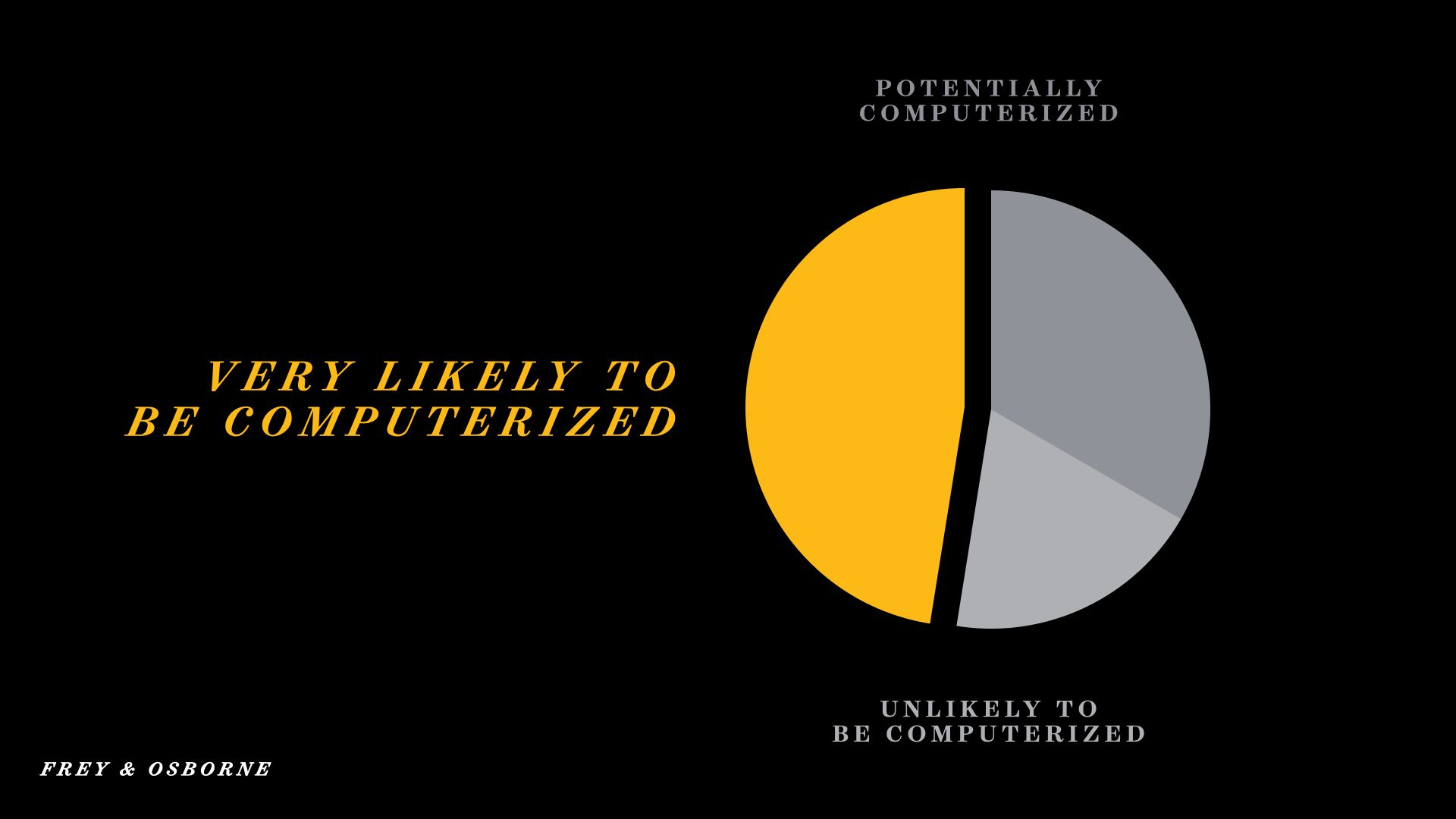

Even if we don’t screw up, these jobs are not going to be with us long: 47% of all work in the US is likely to be computerized in the next 20 years. This includes most jobs at or below the median income. Perhaps we’ll come up with other ways to spend our time, other ways to be compensated, or train our way into new careers, but it’s startling to thing that nearly half of us have jobs that straight-up won’t exist by 2045. If you’re 45 now, and you’re awesome at your job, you’re set — you should be able to ride out to retirement without a computer eating your work. Everyone else should be making alternative plans.

But perhaps there’s a silver lining in all of this — most of us don’t like our jobs, so we might not be sad to see them given to a robot.

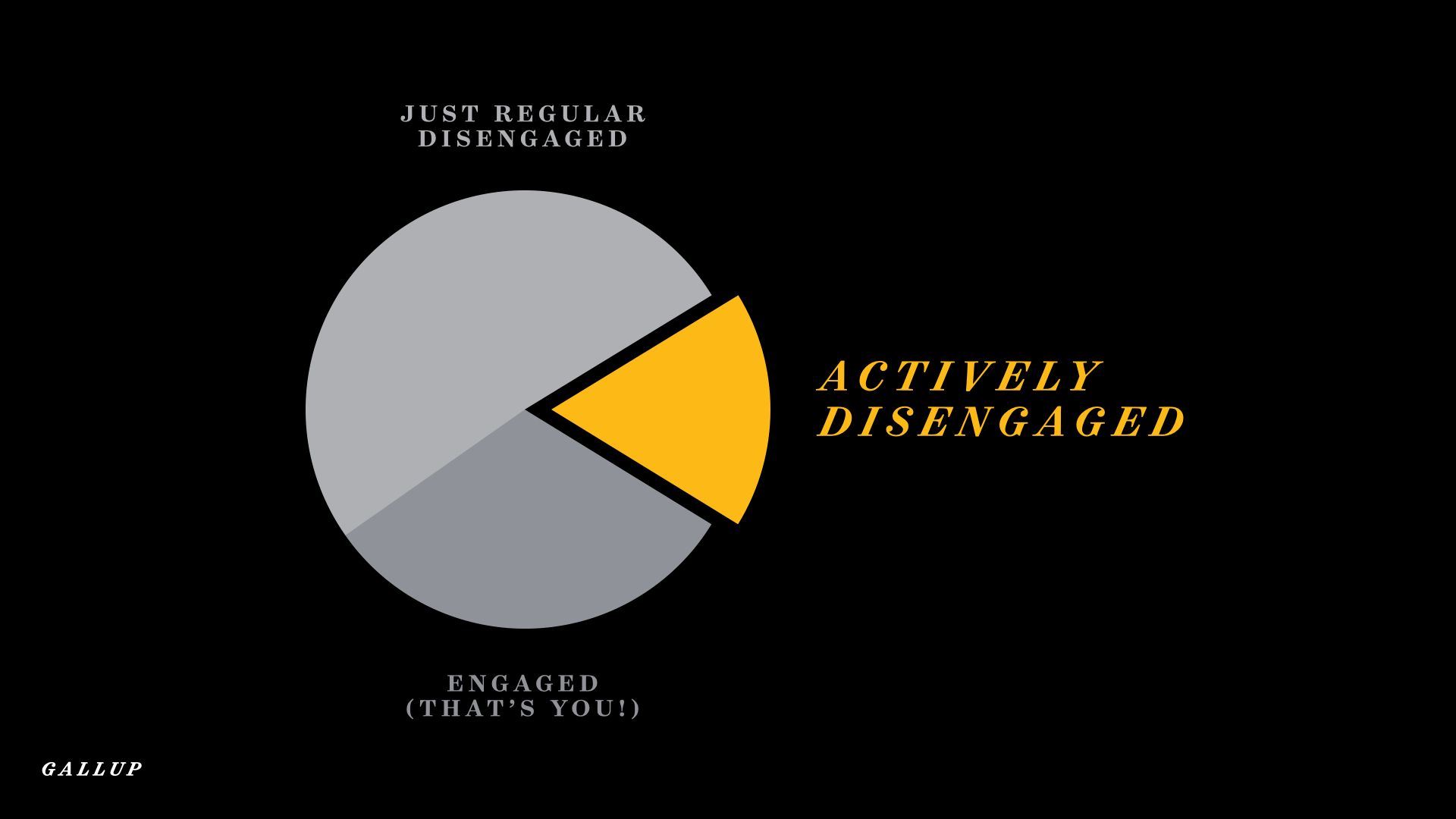

Fully 17% of us are actively disengaged at work, which I can only assume means that we are working hard against our employers because we hate coming to work…but probably stopping short of outright sabotage. The chart from my deck doesn’t do a great job of highlighting that almost 70% of us are either actively or passively disengaged. Seventy percent!

Something is wrong here.

I’ll sum up with two of my favorite, sad quotes about the workplace. The first I found in a tweet, so it might not actually have been said by Cory Doctorow, but I liked it so much that I kept it. The second is from Office Space, which might be one of the better ethnographies of the workplace ever created.

We have fashioned a very bizarre existence indeed — one where we spend a lonely couple hours commuting to and from a workplace that we hate, where we’re quite clearly just cogs in a machine that prints cash for the global elite, nervously avoiding mistakes and covering our asses while we await computerization or redundancy.

Until then, try not to be too bummed out at work — it can get better.

The alternative

So far, I’ve outlined a few of the reasons why organizations are forces for evil. With all of those reasons in mind, I’ll ask you now to consider that organizations are our only hope, and the forces that act on them are becoming more favorable by the day.

Before we get into why this is, we should have a collective understanding of what an organization is.

The organization is an economic device and embodied idea for achieving a shared purpose that requires the work of many people.

Its boundaries are defined by purpose. While important, W-9s do not define who is in and out of the organization: shared purpose and active participation do a better job of this task. An organization is fueled by the time, attention and/or money provided by the people who perform or make use of the organization’s work. Lastly, it is structured by the relationships between the organization and its participants, and within the participant group.

To use a framing from D’Arcy Thompson, an organization is a diagram of the forces that surround it.

Good news, everyone! Today is the best day ever to be a human, and tomorrow will be better than today. Inequality and violence abound, yes — and human suffering makes for a watchable news cycle — but most of the trends detailing the human condition are starkly positive.

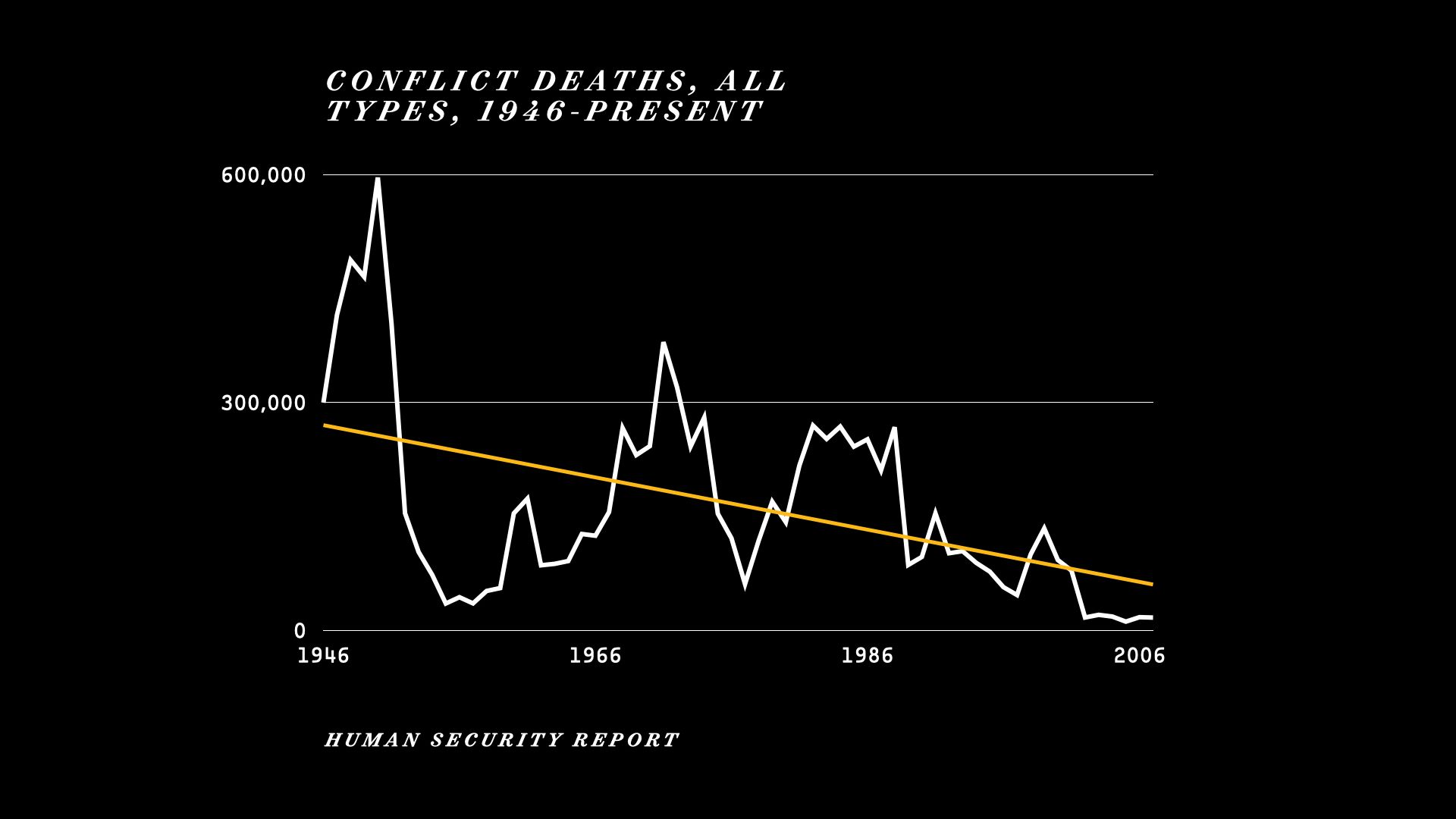

For more people than ever, the world is a safe, productive place. Despite how scary the world can feel, increasing connectedness keeps us safe. I believe that as we become more connected, we’re less likely to act on our anti-social urges, and the sharp decline in conflict-related deaths is strong evidence of this being the case.

Bonus: half of the world is living in some kind of democracy…and yet almost all of us spend our days in workplaces that resemble authoritarian dictatorships. This makes no sense. Anyway.

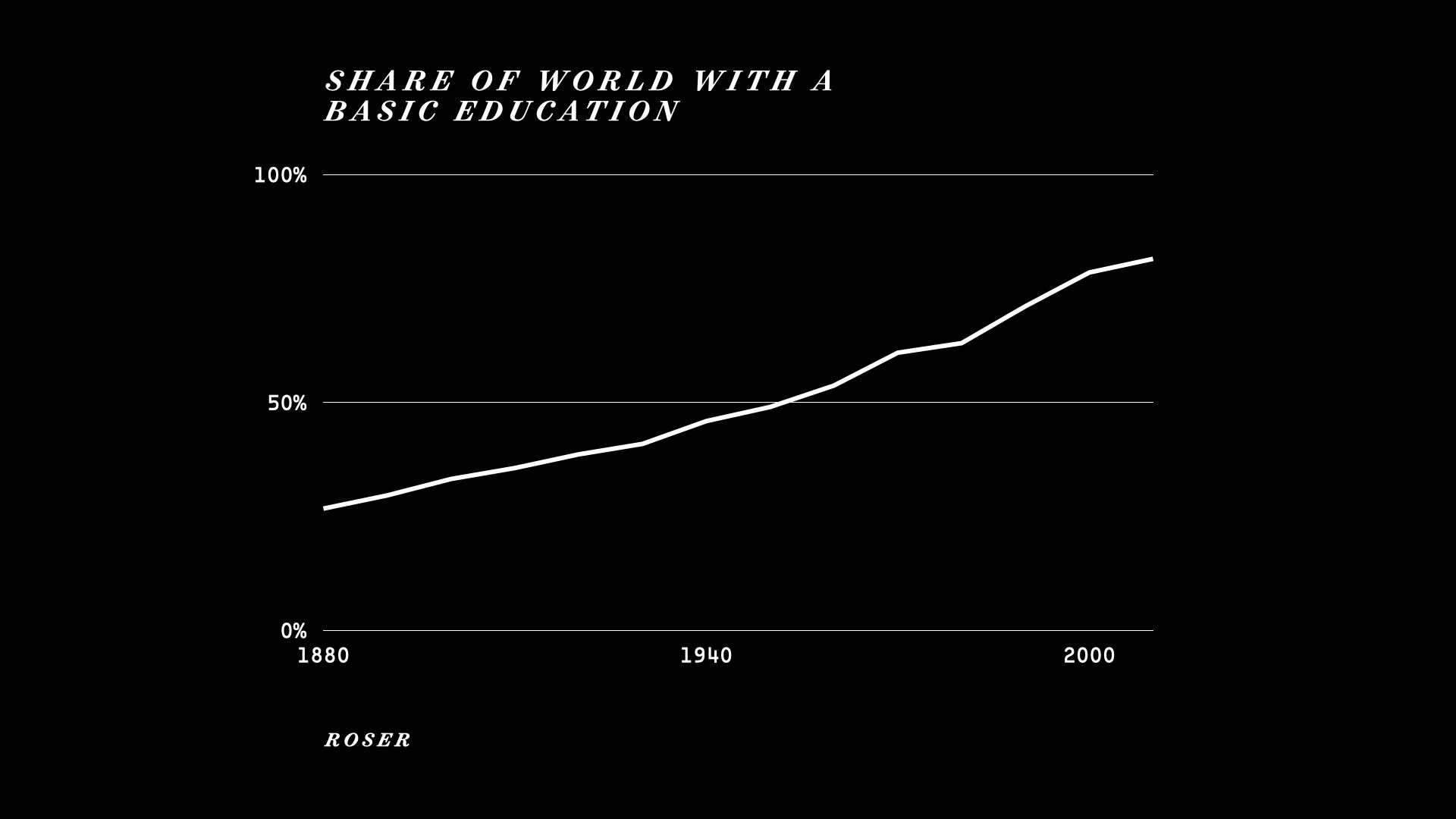

Thomas Piketty contends that the only force pushing toward income convergence is the diffusion of knowledge. Today, more than 80% of the world has a basic education. It’s a widely variable experience that continues to contribute to inequality, to be sure, but it’s moving in the right direction. And this depiction of the education landscape doesn’t take into account the compounding effects of digitization and connectivity. That it’s possible today for anyone with a broadband connection to access something like Wikipedia, or courses from the world’s best educational institutions through EdX or Coursera changes the game for employers and employees.

For employers, it means that you can expect to hire people with ever-improving capacity for creative work. For employees, it means that you don’t have to keep your shitty job. If you have the time, energy and internet connection necessary to learn, you can build skills that increase your employability or make it possible for you to start your own enterprise.

From an organizational context, the key shift is to a lower likelihood of extrinsic loyalty between the firm and its constituents in both directions. Employees are more likely to be replaced by someone with more training, and they’re more likely to set out on their own.

Fun fact: in 1961, it would have cost a quadrillion dollars to build a computer that matched the iPhone 5 in power. Of course, that would have been a silly idea, because it would have taken decades for the entire world to save up enough cash just to fund the project. This is a MacGuffin — it would have been impossible and undesirable to do so in 1961 — but it illustrates the improvement in cost performance for computing power. What would have cost many years of global output to produce is now available for the cost of a few weeks of average global income.

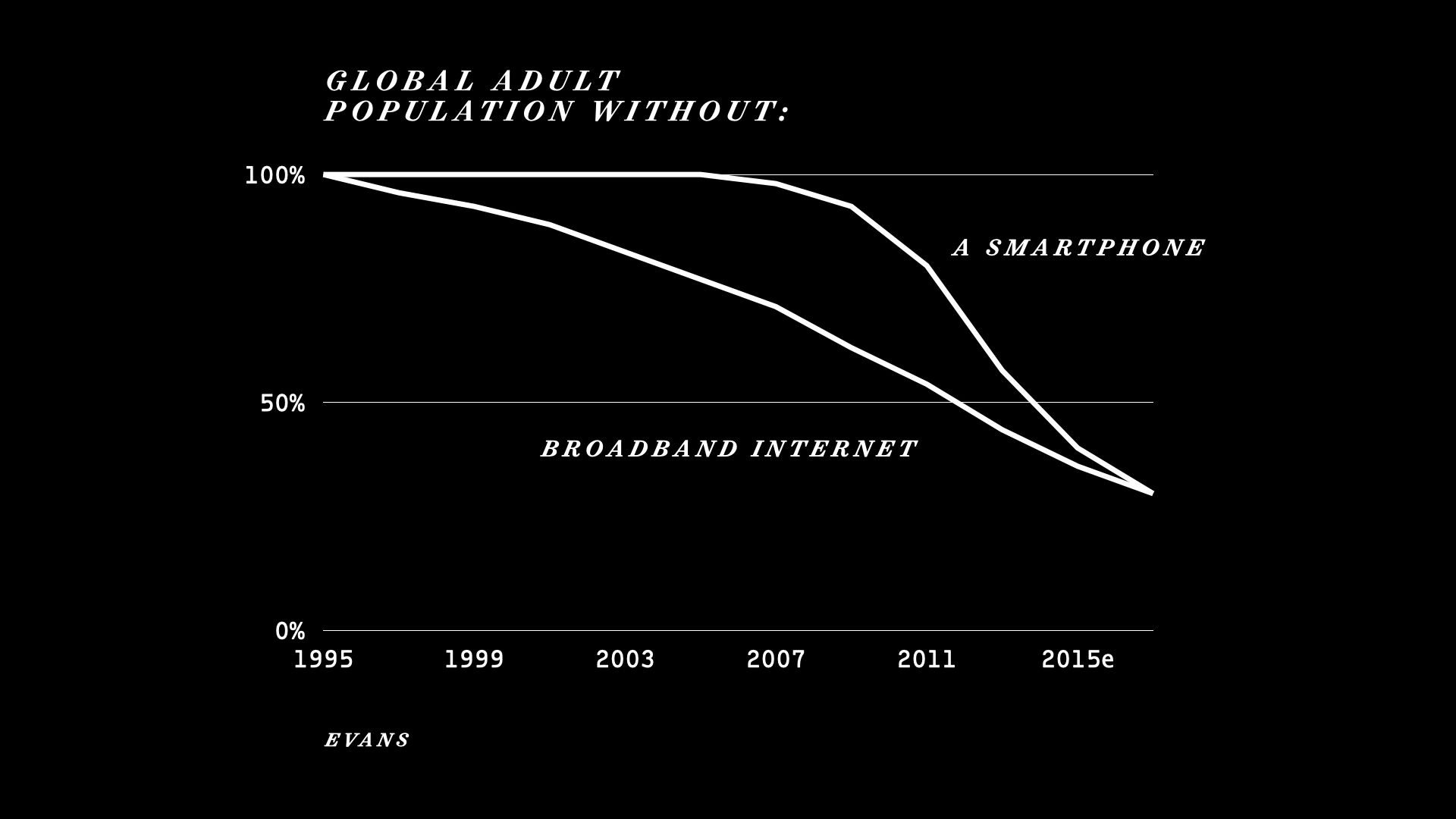

Which allows more people to become connected to one another.

Which along with cost performance improvements across a variety of essential technologies allows for the development of platforms.

Free or paid, open or closed, I define platforms as businesses upon which others can build businesses: AWS; Uber; WordPress; various app stores; Android; Tesla batteries. These platforms take things that used to be really hard to do or build and make them fantastically easy, cheap, and fast. And they change relationships between organizations, challenge the notion of ownership, and put pressure on the fundamental theory of the firm.

Amazon Web Services powers most of the internet, including its main competitor in streaming content, Netflix. Cars and houses have become platforms using Uber and AirBnB. Humans have become a platform unto themselves, with apps and devices that track our biology, movements, and activity. WhatsApp reaches a billion people with five team members that build their Android app.

The platforming of everything will lead to more inequality — the owners of the platforms will be the ones that receive all the wealth — but it will make life easier and enable even more choice.

Hate your job? Get educated on EdX and come up with an idea. Test value propositions using cheap variations on a Squarespace theme. Grow a network on Instagram. Start accepting payments using Stripe. Hire people using WhiteTruffle and grow your team until you can outsource your HR to Zenefits. Et cetera ad nauseam.

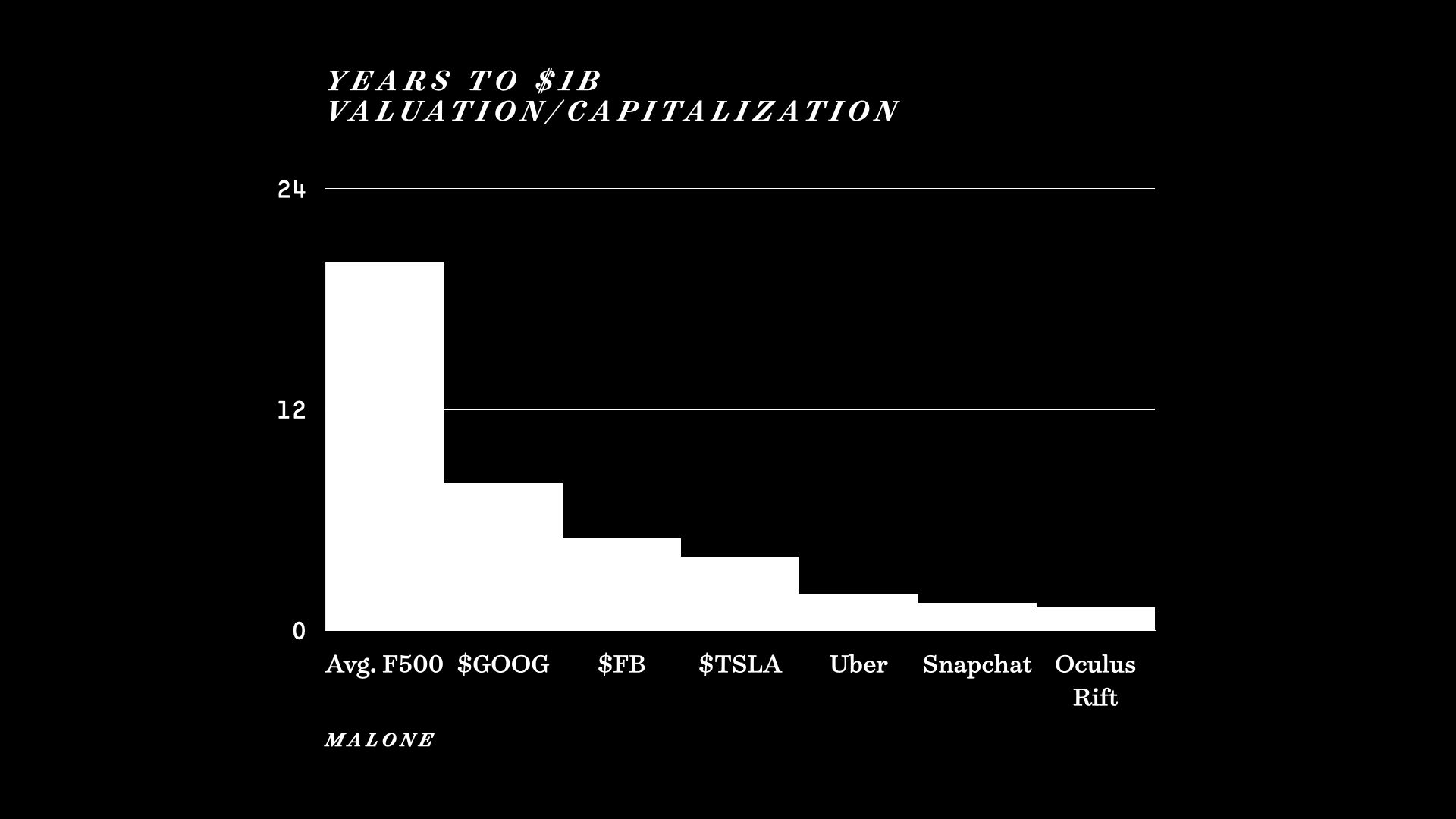

If the idea is good enough, you’re in luck; it shouldn’t take long for you to accelerate into the global elite.

No matter how you explain it — frothy venture markets, low interest rates, increasing economic liberalization, the onrush of technology — there’s no arguing that valid ideas grow faster today than they did in the decades past.

What’s more, most of these organizations can be tiny compared to the sprawling industrial giants of the past. They are exponential organizations, capable of reaching more customers per employee than was previously thought possible.

Wait.

Are organizations degrading the human experience, or are they poised to accelerate our progress toward dignity and achievement in the 21st century?

Yes. Both of those things are true. And this is the time we’re living in — a time of deep, perhaps un-solvable paradoxes.

We should not despair, though — there are some early signals of these organizational paradoxes creating favorable outcomes.

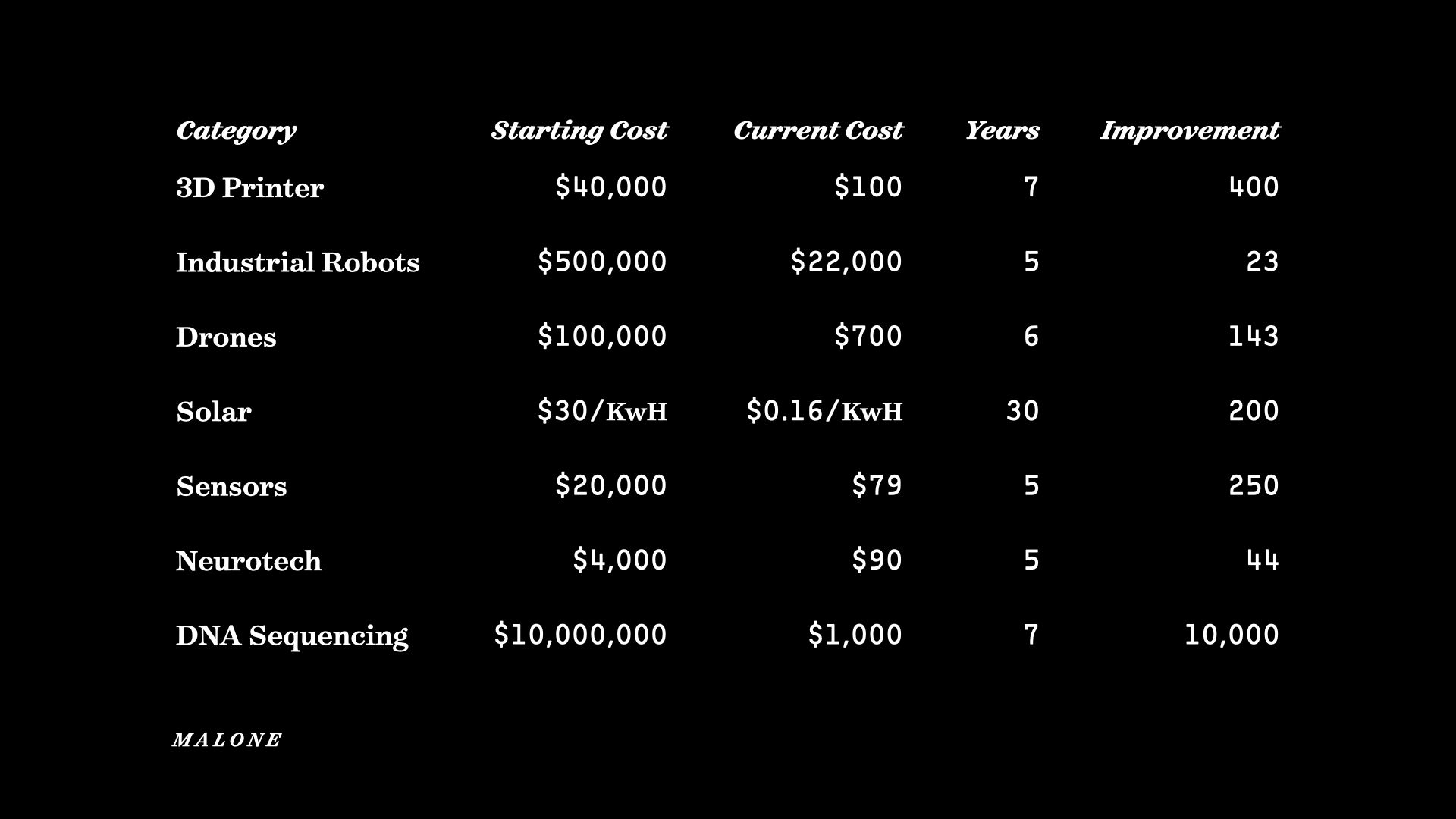

The Makerbot story is a good one. A few friends want a 3D printer, find out it’s super expensive — $40,000 makes the story work best — decide to build their own for $400 in material costs, end up building a company that they sell four years later to a big 3D printer company for $400m.

The final figure is actually $604m, and I have no idea if the $40,000/$400 numbers quoted are 100% correct, but the symmetry is too delicious to pass up and the scales are mostly right.

Factual accuracy aside, the story shows how an open-source platform and community can create real value around an enthusiast-grade physical product. It shows the possibility for rapid growth. It shows that even relatively small investments can create big returns. That the same company they wanted to buy one from at the beginning of the story is the one they sold to makes the story a makes it a nice “fuck you” to the man, so to speak. The news about Makerbot recently hasn’t been so great, which further demonstrates the fickle, transient nature of the world we occupy.

W.L. Gore is my favorite example of 21st-century organizational principles coming to life at commercially relevant scale. They produce a wide variety of physical goods — from Gore-Tex to heart valves — in regulated and (relatively) unregulated sectors.

They have a healthy business, clocking $3b revenue annually, and they’ve been manager-less since their founding over 50 years ago. Not a single manager among 10,000 employees. And they’re making heart valves. If they can do it, you can do it.

Fun fact: they limit the population of their factories to 150 workers.

Caveat emptor: it’s said that it takes six years for the average new employee to become fully operational inside their self-organizing system.

Or Tesla. Tesla is the fucking future. That they can push an update to a car that makes it safer and more autonomous, that they’re not just a car company but also an elaborate ruse to change energy markets, that a good portion of their employees came from traditional auto companies and now are making far better cars than they were before… there’s something special happening there. And they’ve been alive for a decade. A decade!

Hopefully by now you’re looking for some answers.

Why do I hate going to work on Mondays?

Why are we going out of business?

Why can’t we keep up?

Is this the only way it can be?

What’s happening, and what can we do?

One quick answer to a question you might not be asking: Organizations are not broken. (Sorry, I lied.) It’s just that the legacy organizations that we designed 100 years ago are disadvantageous for a world defined by choice and complexity.

The organizations we have today are broken because of accelerating user choice.

Everything we do scales faster than it ever has before. We’re better educated than ever before. We’re smarter than ever before. We’re living longer and more vibrant lives. Work is more creative, and decreasingly physical, so we reasonably can fit several careers into a life. We decreasingly tied to one source of income, as emerging peer-to-peer markets allow us to monetize more of our lives.

This isn’t true for everyone, as our world improves even as it becomes less equal, but in general we have more choices today than ever before. We don’t have to choose the shitty mass-produced option in the store. We don’t have to accept the stultifying mid-level manager role in the faceless multinational. The war for talent and customers isn’t just against your direct competitors — today you compete against everyone for everything. It’s a good thing there’s more to go around.

And because of the platforming of everything, and the disproportionately positive outcomes for the platform owners, in every category there’s an all-out race to the top, where time is the only unrecoverable resource.

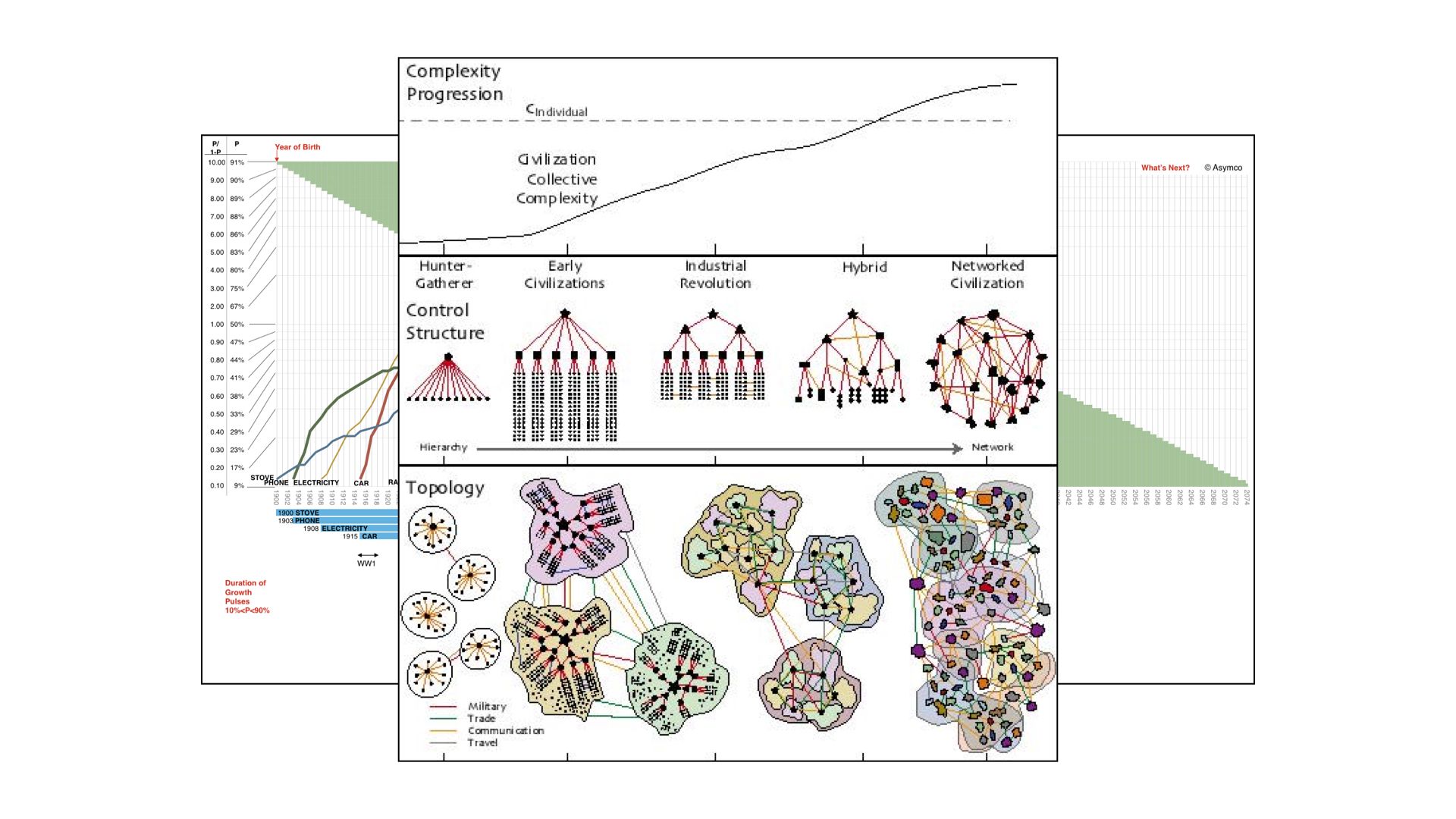

The organizations we have today are broken because of increased connectivity.

Our connectedness grows by the minute, as new platforms, profiles, and devices bring more of our individual lives into contact with others’. Whether we like to believe it or not, our organizations are networked internally and externally, and depicting them hierarchically fails to capture the rich interplay between public, private, department, division, function, leadership, team.

To go a step further, I’d argue that our explicit, bounded tree-modeled structures have been invalidated by connectedness, and that this cognitive dissonance prevents us from maximizing achievement and human dignity in the workplace. Further, it creates so much complexity — more than an individual can reasonably hold in their head — that boss-led decision-making makes little sense. A new model is needed to understand work actually happens, and to push us away from the dystopian work futures that seem so inevitable.

This model needs to be able to span what we had traditionally defined as “company” and “customer” groups, cutting across boundaries of employment and consumption. It’s a model that needs to live in the heads of all members of these networks, and allow for governance to extend from the customer in to the organization itself. It’s a model that must account for more people having more power than ever before, and allow them to help the network make good decisions.

Above all, this increase in connectedness means that structure matters more now than it ever has, and it means that we all can work on it.

The organizations we have today are broken because we’re using models that were designed for a different context.

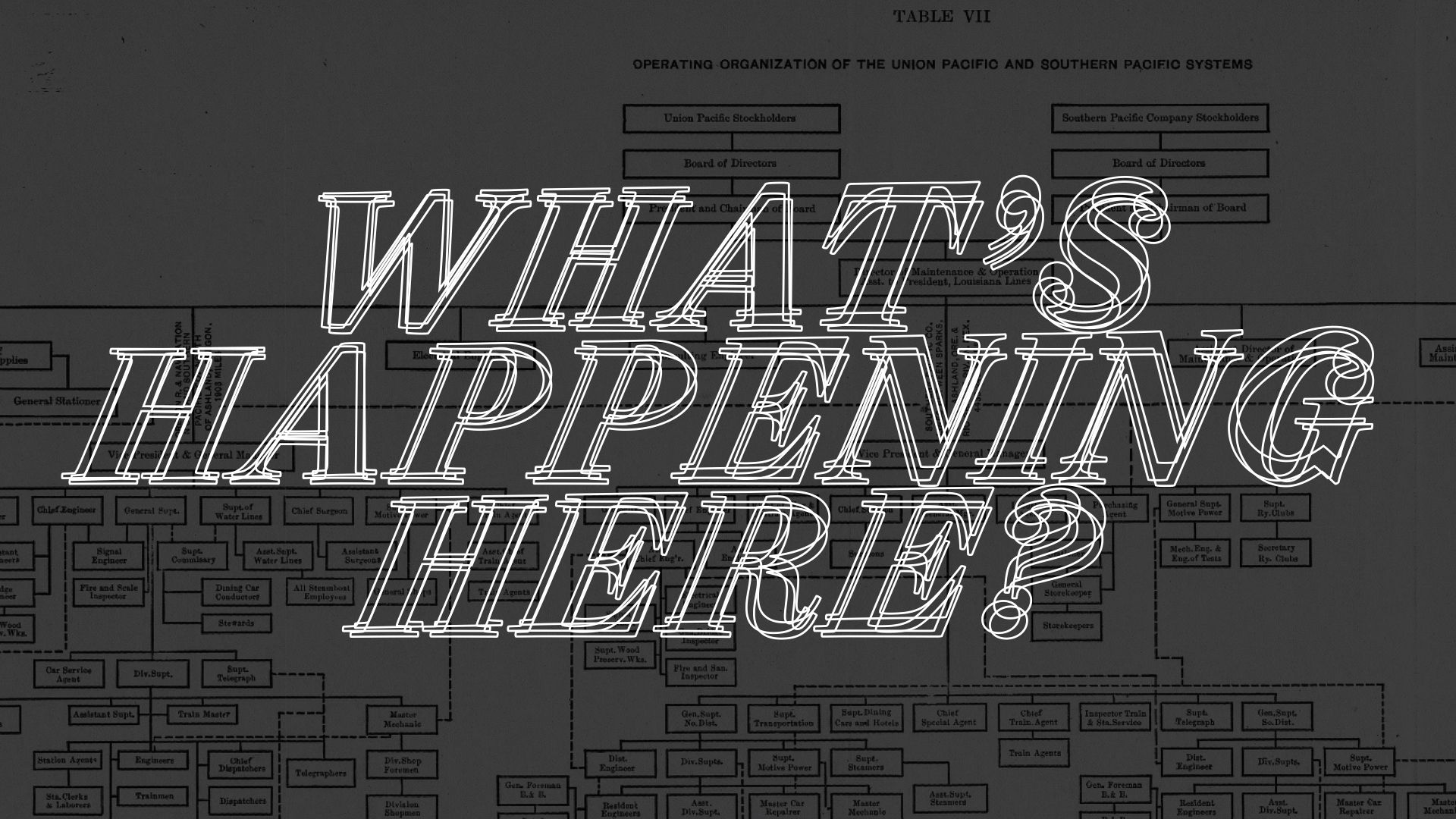

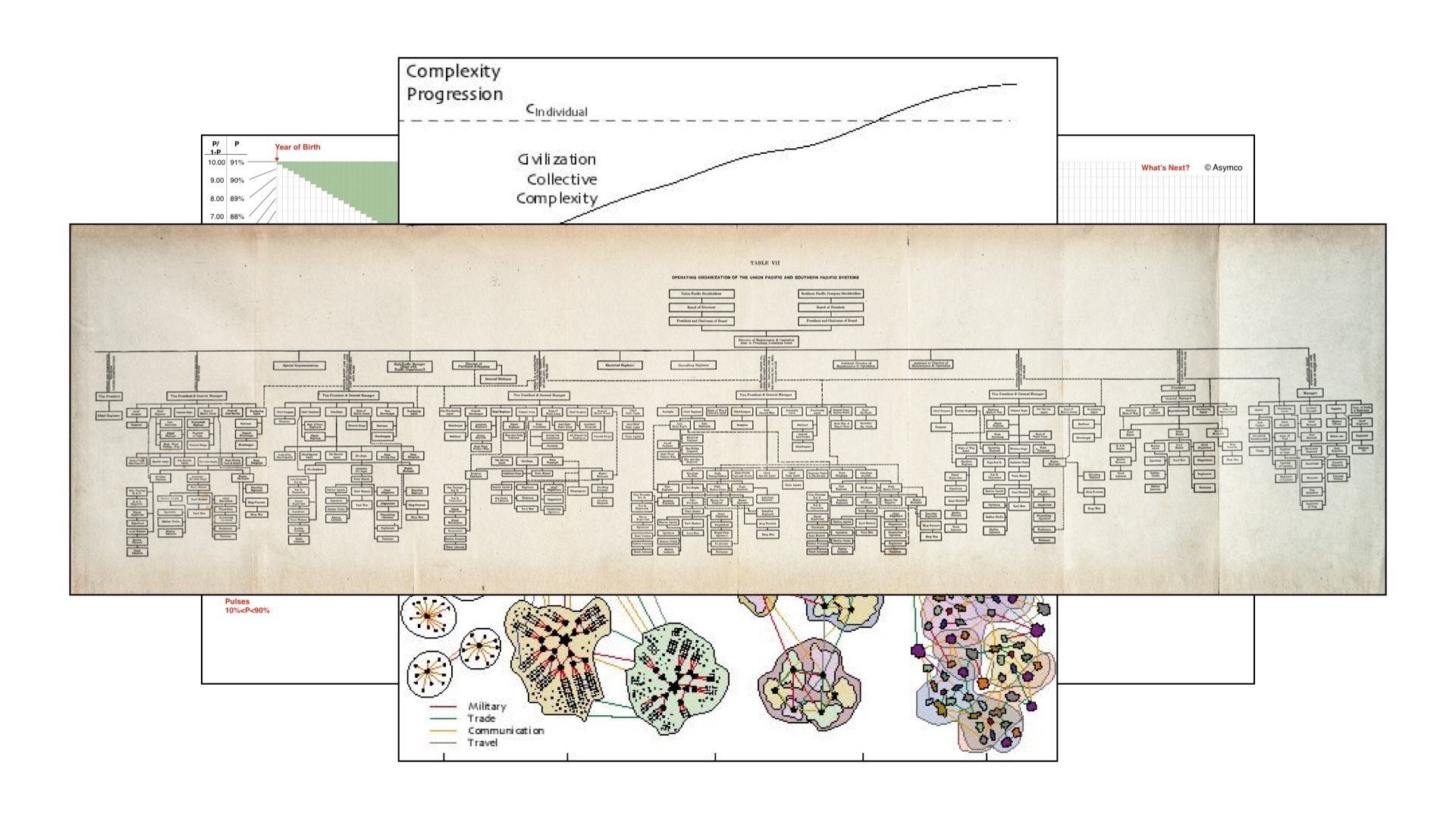

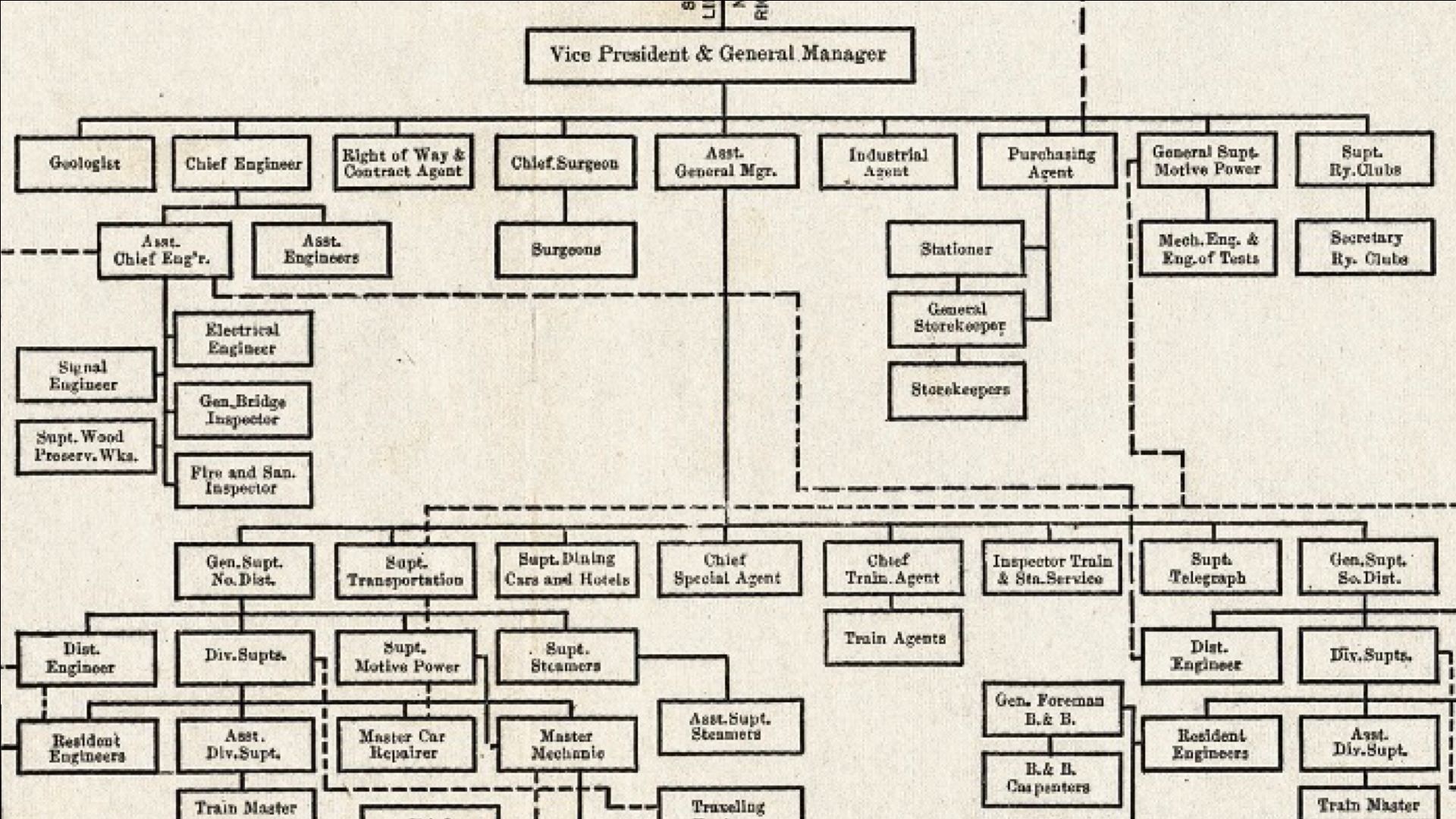

The org chart presented here is from the early 1900s, and it looks very similar to the boxes and lines, dotted and solid, that we use today. These structures were originally designed to separate entrepreneurial decisions from operational work, and are most fit for an organization that plays in a single category, with few products, in markets that reinforce a monopolistic approach to resources. Hierarchies made a lot of great things possible, things that helped a lot in a more certain age: stable, predictable work processes; high-fidelity forecasting; divisional perspectives represented at the management level; centralized shared services; silos of independent work types. And there are plenty of organizations that still use a traditional, command-and-control hierarchy to great effect, with Apple being the canonical example.

(A note on silos while we’re here. Silos are not an absolutely bad thing. It’s good to not have your work messed-with by 9 departments that aren’t yours. It’s good to have some amount of clarity on who gets to decide what, and for those decisions to happen entirely within your team. To wit, 100% dedicated teams are more or less the same as silos, but they’re made goodthrough the use of complete transparency.)

The main feature of these hierarchies is the entrepreneurial and operational division; it was originally intended to distribute specific “how we’re going to get stuff done” authority to large divisions of workers. And the separation largely works well if you hold to it: it keeps executives out of the weeds (and out of the hair of those doing the work) while enabling them to make big market, geography, and product decisions atop reliable projections fed from below. In an age of slow communications, limited education, and few connections, this structure was favorable for most, but it makes little sense today. Things move too quickly, and are too nuanced, to allow for slow distribution of information at the edge to a central decision-making body.

Here’s a fun thing. The big management innovation of the late 20th century — the Matrix Org — was developed concurrently with these entrepreneurial-operational hierarchies. Check out that dotted line between the District Engineer and the Assistant Chief Engineer. That’s the same damn thing as a functional matrix reporting relationship, and pretty close to Spotify’s chapter structure. Back then, it was called a “line-staff” relationship, where you might be a team member on a particular production line, but part of the staff of a functional group.

This should all underscore one critical point: organizational design is the work of small, semantic changes, where everything communicates value. In practice, “line-staff” and “functional matrix” and “chapter” feel very different for the workers involved, and for the customers touched by the structure. But they’re fundamentally the same concept.

All of this leads me to a conclusion. It’s not that organizations are broken. Organized people are the only option we have to get good things done. It’s just that the legacy organizations that we designed a century ago don’t make any sense in today’s world. Maximizing the old ways of working and organizing isn’t going to cut it. But before we start making changes, we’ll need to know what we’re optimizing for — what “good” looks like — and I’ll cover that next. Stay tuned!

Comments